Better democracy via different flavors of proportional representation

Open List PR methods in Finland and Sweden show that the devil is in the details; well-designed institutions must respect a nation’s culture, history and traditions

[DemocracySOS welcomes back Canadian political scientist Henry Milner as a guest contributor. Professor Milner has been on the faculty of Vanier College in Montreal and at Umea University in Sweden, and has been a visiting professor or researcher at universities in Finland, Norway, France, Australia and New Zealand. He is currently a Research Fellow at the l’Université de Montréal, where he is at the Chair in Electoral Studies in the Department of Political Science. He is also co-founder of “Inroads: the Canadian Journal of Opinion,” and has written numerous articles, both scholarly and journalistic, specializing in political participation and electoral reform. He is author of eleven books, including “Civic Literacy: How Informed Citizens Make Democracy Work,” a classic in its field that challenges the “social capital” thesis of Bowling Alone by focusing on a comparative analysis of the effectiveness of democratic institutions; and his recent political memoir “Participant Observer: An Unconventional Life In Politics and Academia,” in which he tells about his eventful life as an academic on several continents, a party leader in Quebec, and a student and community activist in the 1960s and 70s after being born in a bunker in American-occupied Germany. Insider-outsider, observer and participant, academic and activist, his is a “political autobiography of a generation.”]

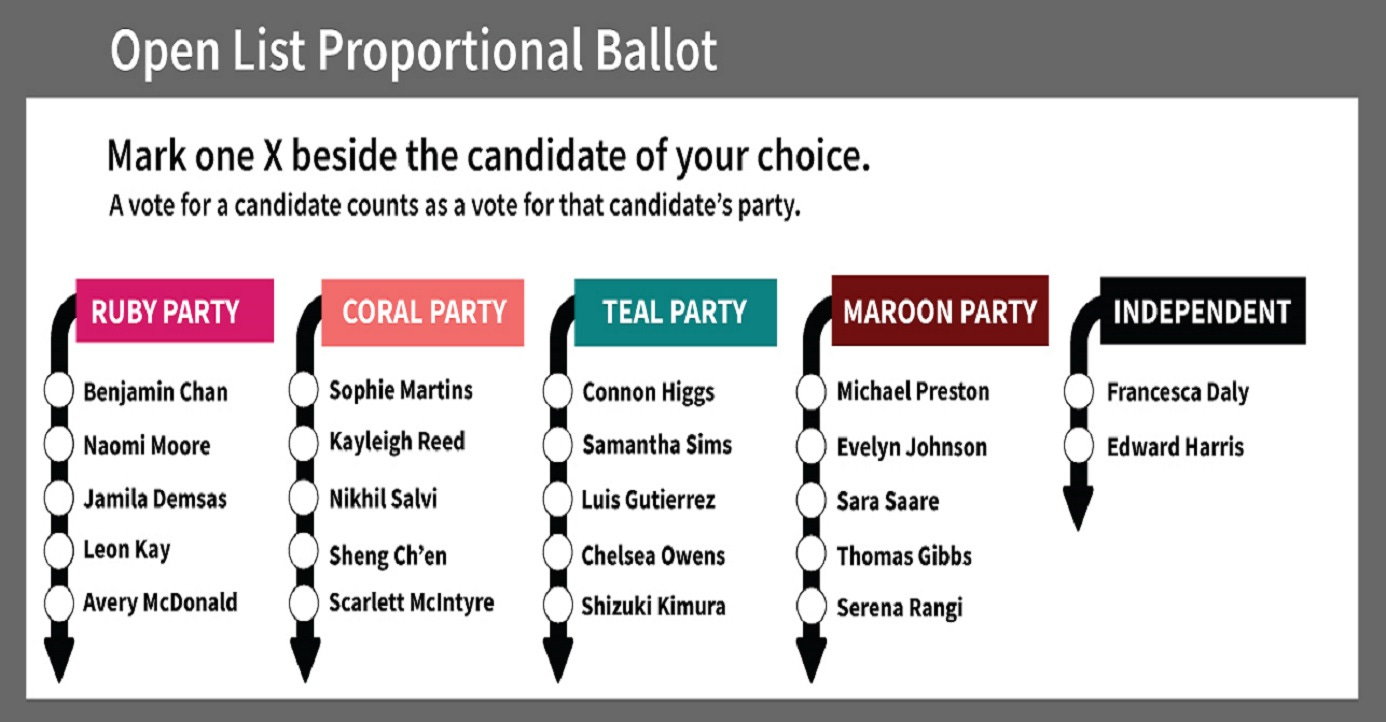

Different nations have created innovative institutions of democracy, based on their own country’s history and culture. Two of the countries in which I have direct experience and knowledge are Sweden and Finland. Both of them use a version of proportional representation known as “open party list,” but with important differences.

Sweden’s “partially open” list PR system

As a Canadian political scientist, I have lived and taught in Sweden as a university professor off and on over 25 years, and closely observed the workings of its political institutions, including the workings of its list-based proportional electoral system. A PR system can be more or less open, and the Swedish system probably can best be described as “partially open.”

To represent a nation of about 10.4 million people, Sweden’s national parliament, called the Riksdag, has 349 members. Rather uniquely, compared to the political systems in the US or Canada, Sweden’s parliament is unicameral.

To win seats in the Riksdag, a party must win at least four percent of the vote nationally, or twelve percent of the vote in one of the 29 multi-member electoral districts with 11 or more seats each (except for the Island of Gotland, which only has 2 seats). 310 of the Riksdag members are elected from the multi-seat districts using open lists composed by the political parties before the election. Like closed PR lists, open lists often have an initial ranking established by the party, but as we will see below, voters have the opportunity to vote for individual candidates.

Another 39 seats are “adjustment seats” which are distributed to the parties in the 29 electoral districts to make up for any underrepresentation resulting from “votes to seats” disproportionalities in the districts. Overall, the number of seats won by each political party will be proportional, as closely as possible, to the distribution of votes nationally.

Eight parties were elected to the most recent parliament, including the center-left Social Democrats which dominated Swedish politics up until recently. Other elected parties on the left include the Green Party and Left Party, while among those on the right are the Moderate Party, the Christian Democrats and the populist Sweden Democrats.

In Sweden's open list PR system, voters have the option of voting for an individual candidate as well as a political party. On the selected party’s list they can add a “personal preference vote” for the chosen candidate. The proportion of votes for the party’s list determines how many of the region’s seats the party is entitled to receive. Those elected will be from the top of the pre-selected list, except that any candidates who receive a number of personal votes equal to or greater than five percent of the party's total number of votes in the district will be automatically bumped to the top of the list, regardless of their ranking on the list.

To some degree this can turn the election into both a competition between parties and between single candidates on the party’s list. But this is not the case very often. Most voters do not cast a personal vote, instead they just vote for their preferred party. Party identity remains strong in Sweden, so most people who vote for a party agree to accept the pre-election ranking of its party’s candidates. So only a relatively small percentage of candidates make their way into the Riksdag via personal votes.

Finland’s “fully open” list PR

I first discovered Finland’s unique electoral institutions during a four-month visit in 1991, based at a Swedish language university in Turku/Abo on the Southwestern coast. I was impressed by what I learned about this country. Finland is the most resilient of the four Nordic countries, having undergone colonization by Sweden and then Russia, as well as invasions and civil wars. Only winning its independence from Russia in 1917, the country was deeply politically divided between left and right which reflected conflicting loyalties towards Russia (to which Finland paid reparations after World War II). It was only in the 20th century that the economically and culturally dominant Swedish minority (now only 5 percent of the population of 5.4 million) ceded its place to the Finnish majority.

When the Soviet Union disintegrated in the early 1990s, Finland was able to overcome its economic dependence on Soviet markets by developing high-tech products and companies, starting with Nokia, based on its world-class system of research and development. Education has been a key factor. In its measure of educational performance in 2019, the OECD’s PISA study found that Finnish 15 year-olds remained near the top in reading, literacy and math, and Finland’s educational system is recognized as among if not the best in the world. Noteworthy here is the role of Finnish women: as early as 1907, a third of university students were women.

The struggles the country went through gradually gave rise to values which prized a wide and durable consensus. Finland’s electoral institutions were created and adapted to overcome this conflicted and polarized history, and over time have made it one of the most consensual of democracies.

In politics, this consensus takes the form of oversized coalition governments, relatively moderate parties even on the “extreme” left and right. Typically, the coalition government is formed based on two of the three main parties, plus a few of the small parties (always including the Swedish People’s Party).

The Finnish electoral system is both a product and a cause of this consensus-seeking instinct. The unicameral Finnish parliament, Eduskunta/Riksdag, consists of 200 Members elected from 15 districts. In all districts, except on the small Swedish-speaking Åland Islands, the allocation of seats is proportional to the votes based on a D'Hondt system of party list PR. While the Åland Islands district elects a single member, the other 14 districts are all multi-member. Proportionality is still high in overall parliamentary results, although results in urban constituencies tend to be more proportional. And there are no additional “adjustment” seats to reduce disproportionality, as in Sweden.

Its list system can be viewed as the most open of open list systems: indeed in some ways it’s not really a list system at all. In effect, there is no party list since the candidate names on the ballot associated with a party are not ranked pre-election, and the voter can only vote for individual candidates associated with his or her chosen party.

As a result, the election of a party’s candidates depends entirely on the number of individual votes he or she receives. The voter picks the allotted number of his or her chosen candidate and writes it down on the ballot. The votes cast for the candidates associated with a party are then added together to determine how many of the region’s seats the party is entitled to receive. In Finland’s very open system, the election is truly a competition between both parties and single candidates to see which candidates from any particular party will get elected. If the final result is that Party A is entitled to 3 of the 12 seats in District B, the three candidates from that party that receive the most votes are elected.

The Finnish system works well as a proportional system because Finland is a small, well educated, relatively homogenous country where voters can be expected to know something about the candidates in their region. A total of 10 parties currently have seats in the Eduskunta/Riksdag. The three main parties are the center-left Social Democrats, led by current Prime Minister Sanna Marin, the rural-based Center party and the center-right National Coalition Party, whose former leader, Sauli Niinisto, in 2018 was reelected to the largely ceremonial position of President.

As the D'Hondt formula of allocating seats favours large parties, small Finnish parties usually take the opportunity of joining an electoral alliance with one or more parties. Electoral alliances are made at the district level, which means that one party can join a different alliance in each district. Most small parties join electoral alliances, which reduces disproportionality between votes and seats and ensures only a small number of votes end up not contributing to electing a candidate or party.

One notable aspect of Finland’s unique electoral system (Estonia uses something similar) -- parties sometimes recruit celebrities (e.g., hockey stars) as candidates to boost their ticket. But this is rare: This might not be the case if a more celebrity-oriented country were to use the same system. What is more important is that the parties work together well in the parliament and in the coalition governments, in which deputies from the small parties can play a useful role. One such example is the role played by the small Swedish People’s Party, which is always a member of the ruling coalition.

Due to the relatively low level of income inequality, and perhaps also because they have a historical memory of the hard days and how far they have come, Finnish citizens report extraordinarily high levels of life satisfaction. In 2021, the World Happiness Report announced Finland to be the happiest country on earth for the fourth year in a row.

Political stability in Sweden and Finland

Clearly, the Finnish system of proportional representation has been an important factor in Finland’s overcoming the obstacles it faced and continues to contribute significantly to its achievements. It’s a method that fits well with the Finns’ culture, traditions and history. It is worth noting that faced with Mr. Putin’s aggression in nearby Ukraine, the Finnish parliament came to a rapid and clear consensus that its longstanding non-aligned position was no longer appropriate and voted to apply to join NATO. This is a country which deserves more international attention than it receives.

When it comes to the electoral system, it is Sweden’s PR system that deserves more attention. The Swedes have arrived at the appropriate balance between proportionality and individual choice for Sweden, one that could well serve other jurisdictions. Many US states could benefit from trying the Swedish system for state legislatures. Voters would still be able to vote for individual candidates yet enjoy the benefits of proportional representation, including multi-party democracy, more choice for voters and more women getting elected.

The Scottish method called Additional Member System (AMS), in which most representatives are elected by single-seat districts and combined with a topping off of "additional members" to ensure parties win seats in proportion to their overall vote, could also work well in US states. I will write about that in a future article.

Henry Milner

The use of party voting in list PR, and MMP as well, may be unpopular among voters who are used to voting directly for a candidate.

Overall top-up levelling seats are likely not available in Canada where, constitutionally, votes may not cross provincial boundaries, as each province must have its own discrete representation - as in so many seats for this province, so many for that.

Multi-member districts with fair voting may achieve as fair rep. as list PR or MMP, excepting the most dispersed parties with shallow support. fair voting meaning STV or list PR.

Many list PR and regionalized MMP (Scottish-style) use as low District Magnitude as is available under STV. West Australia recently conducted STV election electing 37 members. Few list PR systems use DM of less than that, or at least only some use DM larger than that.

That wide DM does mean lowering of concept of local representation. so either causes or reflects more party-based thought than local sentiment.

Fine if party means true sentiment of voters (while of course local rep. has been blinded by historically being based on myth that a single-member can represent all those who happen to be penned in a micro-district that covers just part of a city.)

But if party means votes are funnelled into approving the agenda of party insiders, then not so good.

A multi-member district in many cases will cover just what a single member repesents in other contexts.

Everyone living in a city-wide district is represented by a mayor. therefore such a MMD can hardly be said to be too large to be one district, when one member represents that many. If one can cover that size, then surely five or 7 or 12 or whatever number of multiple members should be able to.

And that mayor, like a local sports team, is (or should be) seen as being local enough.