Democracies vs. authoritarianism

Americans’ prejudices about China cloud our understanding of both China and our own representative democracy

Is democracy passé? Is it a spent force in the world’s evolution? In recent years, the reputation of representative government has been under siege from authoritarian governments and elected illiberals like Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán. In this lightning fast age of digital media and transactional politics, even many in the West have been declaring that China will soon rule the world, that its rise is a “powerful challenge to the liberal international order,” that the “future is Asian” and that “democracy is losing the fight” to the “dictator’s playbook,” which will result in the “end of the Western world” as we know it.

Certainly, due to the sheer size of its population—one-fifth of the world’s total—China has become a global leader in economic output, trade, resource consumption, carbon emissions, and pollution. Signs of modernization and increasing affluence for a small but growing segment of the population are plain to see. It has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty — but with a population of 1.4 billion, it still has hundreds of millions more living in difficult conditions, with a low per capita gross domestic product of $12,000 per year (which is about a third of its Sino-rival Taiwan, at nearly $34,000, and barely a sixth of the US at $69,000).

Some experts have likened China’s political trajectory to that of a meritocratic “consultative dictatorship,” in which the leaders use various public opinion technologies and citizen assembly-type deliberative forums to presciently keep their fingers on the pulse of the people and meet their needs, a kind of twenty-first-century version of Plato’s philosopher-kings ruling for the good of society. As recently as early 2020, following the outbreak of the global Covid-19 pandemic, stumbling policy responses from various democratic nations seemed to reinforce this perception. The U.S. and Europe struggled to balance public safety with the economy, and individual liberty with personal responsibility, as infections and deaths climbed and lockdown restrictions kicked off protests with deeply bitter partisan ramifications.

But in China, where the pandemic originated, the mostly smooth rollout of nationwide testing, tracking and lockdowns was trumpeted by the ruling Communist Party as proof of its superior governance model. “Dictators get stuff done and are better crisis managers” — those initially seemed to be one major lesson on offer from the “China model.”

What a difference two years can make. Now it is China whose economy is staggering under ongoing draconian lockdowns, even as new Covid variants have caused infections and deaths to surge throughout the population. Lacking the right kind of salutary vaccinations, public trust has eroded and now protests have spread from city to city like their own kind of contagion. In a new wrinkle, a number of the demonstrators have challenged not just the severe restrictions but also the authority of President Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party. Such widespread popular defiance is a rare occurrence in China.

So currently, China looks like a clumsy, flat-footed authoritarian dictatorship that is barely holding its act together. Add in President Xi’s bro-mance with Vladimir Putin and Russia, who so far has bungled the invasion of Ukraine despite having overwhelmingly superior firepower, and suddenly the democracies aren’t looking so bad. For now, at least.

The real China is very different from the over-hyped, over-feared China

China has long played the role of a kind of Rorschach test for many Americans, including political leaders, who have a troubling habit of projecting onto its relative rise whatever threat they need to justify their own belligerent posturing.

I remember speaking at a Washington DC event hosted by the European People’s Party, which is the center-right party in the European Parliament. These parliamentary members were conservatives, so besides myself they had invited several members of the US Congress, who they assumed to be their ideologically conservative counterparts. I have always been puzzled that European conservatives refuse to recognize that, by and large, they are often politically to the left of, not just the Republican Party, but even the Democratic Party on many issues. Many Republicans would be considered far right, some of them even the far-out right, on the European spectrum. “Tens of millions of people should not have healthcare? Say what?” Not even the far right parties of Europe believe that.

The topic of one panel was “How the West should respond to China’s rise.” It was 2011, and much concern was rattling around capital hallways on both sides of the Atlantic over China’s growing economic, technological and military clout.

One Republican House member, representing Virginia, rose for his remarks. With great bombast he proceeded to inveigh against what he called” the greatest threat of all from China.” All waited for his brilliant elucidation. “The trouble with China,” he began, “is that they are all atheists. They have evicted God from their midst!”

Evicted God? Say what? I watched with amusement at the faces of the European MEPs freezing in place, stone flat, as they shifted and glanced at each other uncomfortably. They had just come face-to-face with the vacuousness of the far-out right-wing of the GOP, and it didn’t fit comfortably within their transatlantic frame.

Unquestionably when it comes to China, the hype in the US has long outpaced reality. To understand the “real” China, it is necessary to see it through the double lens of its paradoxical condition as both a major economy and a still-developing country. China is filled with contradictions and serious challenges, and when one grasps the big picture, it’s clear that China has been barely holding together its leaky ship.

When I visited China in August and September of 2008, to conduct research and interviews just after the Olympics, the country that I saw, whether in Shanghai, Beijing or the rural areas, was a long, long way from being a global leader in any meaningful sense. Not much has changed since then. Nearly 300 hundred million people are still migrants, over one third of the working population, chafing at their lowly status and rotten wages. Inequality is rampant. Returning from the rural areas — where the vast majority of Chinese still live — to the cities is like a form of time travel, moving from feudal conditions where plowing is still done by water buffalo to a land of impressively jutting skyscrapers. For most Chinese, life is still a struggle and will remain so for years to come.

Much has been said about China’s astounding economic growth rates. But what has not been widely recognized is that more than 55% of China’s overall exports and 82% of its high-tech exports are made by non-Chinese, foreign companies. Foreign companies based in China essentially reprocess imports of semi-manufactured goods that are then shipped to the US and Europe, China’s largest trading partners. Back in 2007, British political economist Will Hutton made the observation that China remains in essence a subcontractor to the West, and not much apparently has changed in that regard either.

Today there is TikTok, Lenovo (which bought IBM’s consumer line of PC products), Tencent (entertainment and video games), Alibaba (e-commerce), some big banks and oil and energy companies. But China’s authoritarian government, and the political control it exercises over these companies, raises national security suspicions among Western governments and companies, thereby limiting their potential market share and appeal. Add to all that epidemic levels of corruption, whether in banks, the legal system or the political leadership at national, provincial and local levels, which causes an annual economic loss estimated by the economist Hu Angang at approximately 15 percent of GDP.

China — the not so super superpower?

The hallmark of a great power — indeed, of a superpower — is when other nations want to emulate you. What made the United States the great power of the post-World War II era was not just its military might but its economic promise and political and personal freedoms, which caused people from all over the world to want to flock to our shores. Plus post-war America spawned a thousand flowers blooming of different forms of entertainment; for many around the world, the US projected an aura of the good life, the “Land of Fun.”

The City on the Hill, imperfect as it has been, has inspired many people toward an ideal. But no one is banging down doors to get into China. And only the poorest of Southeast Asian, Middle Asian and African countries, virtually all of them ruled by troubled, authoritarian governments, take their development cues from the so-called People’s Republic. China inspires curiosity with its ancient history and huge population, but not envy or emulation.

That lack of soft power appeal will not change anytime soon, and perhaps not ever, unless China at some point opens up its political and economic system. It will remain difficult for China to build great brands or companies, or become a wealthy place that inspires talented immigrants to move there, as long as it remains a one party authoritarian state. Indeed, China would be better served by returning to some of the successful experiments with local and regional democracy that had begun under previous President Hu Jintao, but which President Xi has largely abandoned.

There is no problem in the world today that can be resolved by “more dictatorship.” But quite a lot that can be helped by “more democracy.”

China is our mirror reflection — why don’t Americans value democracy?

Given this more complex reality, why does China receive so many rave reviews about its economic performance while far more prosperous democracies like Japan and various European nations — which actually do a far better job of providing for their people — are treated with scorn and derision by so many US observers?

The answer seems to boil down to the fact that China’s high-growth economy has become the place where US corporations have been able to realize the quickest return for their quarterly profit sheets. Indeed, China’s super growth rates have become an ideological weapon in the hands of free market fundamentalists and pro-growth zealots. The Chinese economy and its high growth engine has been used to browbeat other countries viewed as growing insufficiently. In an ongoing policy battle between free marketeers and everyone else, China has been a useful propaganda tool.

Yet many European nations and Japan are proof that high growth economies are not necessary to create the highest living standards in the world. When yours is still a developing country, the lower costs of cheap labor and natural resources spur global companies to invest, which results in higher growth rates even as the economic benefits are not always broadly shared. But the rate of growth inevitably declines as the size of the economic pie grows in more developed and “middle income” economies. Within these economic constraints, the most advanced democracies have proven they can handle the long term challenges of economic development and social redistribution of the resulting prosperity.

In the meantime, the “China as superpower” hype actually is damaging China itself. It causes paranoid members of the U.S. Congress to propose economic protectionist and militarist measures amidst national security hysteria, when in reality China needs different forms of assistance from the US, Europe and other developed powers. The the prospect of gargantuan China as a failed state is too terrible to contemplate. The entire world has a stake in China succeeding, both economically and in reducing its carbon emissions. To combat the impacts of climate change, we have no choice but to induce cooperation from this modernizing “ancient civilization.” Ditto, to ensure a geopolitical balance that knits together the world’s nation-states in solving the many global challenges. A US-China rapprochement could calm down Putin’s imperial overreach in his near-abroad, and could co-partner in African development.

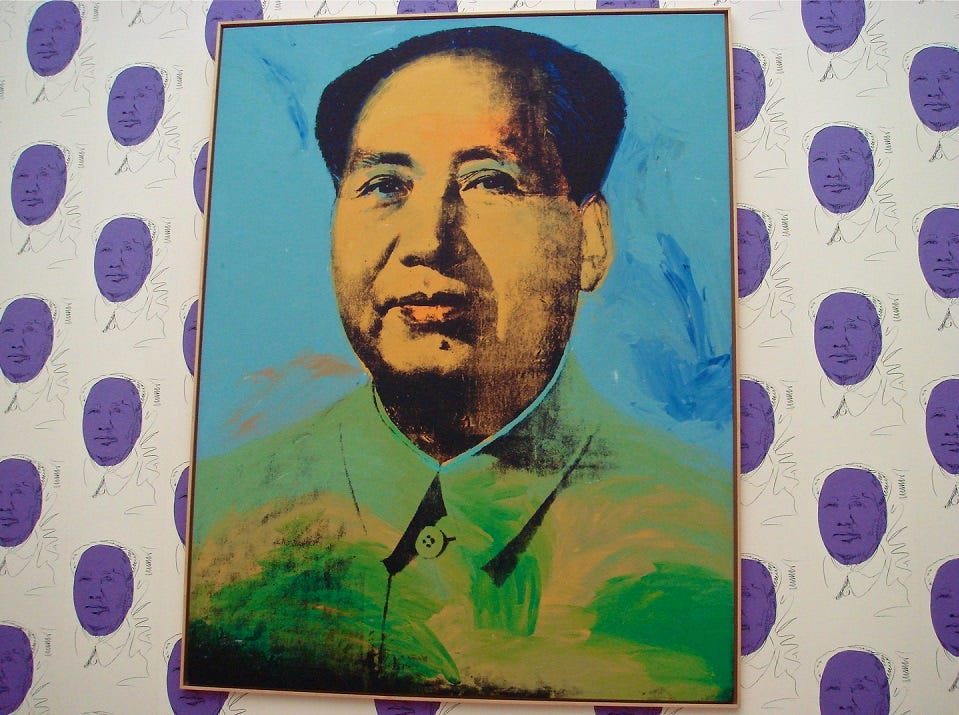

But the Chinese leadership must continue to meet the West halfway. China under Mao experienced economic disaster and grinding poverty. It is only by opening itself to the world in an imperfect spirit of cooperation and partnership that China has developed its capacity that has fostered a rising middle class. In the Chinese government’s troubled Covid policy, the curtain has been pulled back from the over-hype to reveal that it is a modernizing yet still developing country. It remains to be seen how much of a “new China” will continue to emerge, but all these horizons certainly provide a different view of China from the one typically given by the Sino bashers and fearmongers, as well as the mindless free marketeers.

Representative democracies certainly have their challenges and problems, and some are working better than others. But on the whole, Winston Churchill got it right when he said, “Democracy is the worst form of government — except for all the others that have been tried.”

The cautionary tale from China makes me wonder: why do so many Americans have so little value for their own representative democracy, that they would seriously consider China as a model for envy or emulation? And what is it about authoritarian leaders that have always held appeal for so many Americans, making our own long contested struggle for democracy an unfinished business, and one that was dealt a hostile blow on January 6, 2021?

Steven Hill @StevenHill1776

Democracy is hard work. Building consensus requires loads of time and compromises. It's easy for people to fall in love with the "efficiency" of authoritarian regimes until their freedom and money are at risk of beging taken away. And most of us are in denial that would not happen to us. I wish more people would go to Taiwan and watch how people there passionately defend their democracy every 4 years.