Fascists, far-right and neo-Nazis on the loose

Do Italy and Sweden show that proportional representation leads to the election of extremists?

I have to chuckle sometimes at the US media and its coverage of other countries’ elections. In its perennial quest for scare headlines that grab readers’ eyeballs, it throws around the “fascist” label with reckless abandon.

For the past month I’ve continued to see a number of news articles and blog posts claiming that Italy and Sweden have elected fascists. This scaremongering often comes along with bromides and lectures hinting about the dangers of multi-party politics, of electing small fringe parties, which in turn is an indirect attack on proportional representation electoral systems that are understood to be the mechanism for such multi-partism. In tapping into this cultural meme, the logic seems intended to make Americans swell with pride over our own allegedly stable, moderate two-party system.

Which seems laughable in the aftermath of January 6, and as we sit here on the cusp of whatever only-in-America hell storm awaits the nation during this upcoming November 8 election, and beyond that in the 2024 presidential election.

But hey, what about those Italian fascists, and what does their rise portend for Italy, the European Union, transatlantic politics, planet Earth, and while were at it, let’s throw in Mars.

This is not the first time that we have seen such inflammatory headlines. In the past, the temporary ascension of far right leaders like Jorg Haider in Austria, the Le Pens in France, Pim Fortuyn and Geert Wilders in Netherlands, resulted in outbreaks of fawning American patriotism over the alleged superiority of our political system.

But this myth has always suffered from terminology confusion. Virtually all of these "far right" political parties are to the left of the Democratic Party on most issues, as is the European political center in general. In all of these countries, universal healthcare is the norm, whereas even after Obamacare 28 million Americans still lack any kind of health insurance. No far right leader in Europe would ever dare to suggest that 9% of their fellow countrymen and women should be denied access to health care.

Besides universal health care, most European countries also have free or low-cost university education; comparatively generous retirement for their elderly; an average of five weeks paid vacation, more sick leave, parental leave, and a shorter work week with comparable wages for their workers than we have in the US. In some countries, the far right parties have attained their electoral successes by defending the comprehensive social support system that the Social Democratic/center-left parties had been rolling back in the name of fiscal responsibility (known as “austerity”).

While most of the European parties and leaders that fall under the fuzzy rubric of the “far right” have strong anti-immigration views, theirs are no more harsh than Donald “Build a Wall and Imprison Children” Trump or the MAGA madness that now grips the soul of the Republican Party. And in some cases, their anti-immigrations views are actually more benign. For example, some of the European far right parties have found electoral success by promising to impose longer waiting periods before new arrivals can enter the country’s cradle-to-grave welfare system. I remember in particular the hue and cry when the far right party in Denmark demanded that immigrants must wait up to seven years before receiving their benefits. I could only think, “Goodness, how many natural born Americans would be overjoyed at the prospect of waiting a mere seven years to attain the level of benefits bestowed upon Danish immigrants.”

If that is fascism, it comes with a softer rod. Indeed, if one actually takes the time to read the platforms or listen to the speeches of Europe’s far right leaders, one is struck that, once you get past the provocative rhetoric, the far right in Europe does not question or call for the abolition of the European social support system. And looking at this phenomena over time we can see that, just as the far right has won its share of legislative seats, they eventually lost many of those seats as well, and then fell out of coalition governments.

Populism is not always fascism

Meanwhile, the public’s support for such parties is less an endorsement of what they say as much as it is an Everyman’s appreciation of what they do: they poke a populist thumb into the eye of the system.

“What we are seeing is the rise of anti-establishment parties that promise something radically different,” says Sam Van der Staak at the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA). “Right-wing, left-wing is a misrepresentation. It is really about citizens expressing that they are not happy with politics and what the whole system of government is delivering.” Populism pits everyday people against elites, and the rhetoric can get quite inflammatory.

Brett Meyer, a research fellow at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, says there is one burning issue that unites right-wing populists. “If I had to summarize them all up, I would say they are anti-immigrant parties,” he says. “They have all done well in countries where immigration is a salient issue.”

Whither Italy…

These dynamics in great measure explain the vortex swirling around the new right-wing coalition government in Italy. The newly sworn in Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, the first female executive in Italy’s history and supposedly a fascist, has already begun backtracking on some of her more provocative statements. She has renounced the fascists of old as well as her previous anti-EU stances (the fact that Italy is receiving billions of dollars in post-pandemic aid from the hand of the EU cannot be bitten or ignored, even by bombastic populists); she has reversed and announced support for Ukraine, as well as other positions that don’t sit well with her right-wing coalition partners. The fate of this coalition may well follow that of the previous populist newcomer, the Five Star Movement, that was initially overhyped as the future of Italian politics. Since its breakout success in 2018, the FSM has lost over half of its vote share and has become another Italian sideshow.

The same is true for the right-wing Sweden Democrats. It’s flash in the pan is likely to be so quick that if you blink twice you will miss it. The center-left Social Democrats won almost 50% more votes and seats than any other party in the 2022 election. But the center-right coalition, including the Sweden Democrats, the Moderates and the Liberals, together hold the slimmest majority – by a half a percentage point, 176 seats vs 173 -- and have formed a “strange bedfellows” government. They do not have a lot in common.

Meanwhile center-left governments in other countries, after experiencing some difficult years and losing power, have had a resurgence too. But you don’t hear much about that from US media outlets. In Germany, by far the most populous nation in the European Union, the Social Democrats have emerged as the head of a three party coalition government. In Norway, the left-wing opposition returned to power in an election hard fought over climate change, inequality and oil production. Center-left governments are in power in Spain, Portugal, Denmark, Finland, Slovenia and Ireland. The French government under President Emmanuel Macron also leans left on certain issues and easily defeated his far-right opponent Marine Le Pen.

This is just the ebb and flow of multi-party democracy in Europe, founded on proportional representation and other institutions that foster broad representation and vigorous debates over policy. As noisy and as provocatively outrageous as they can be, the far right parties actually do raise substantive issues, particularly regarding the very tough issue of immigration, that the larger, mainstream parties tend to ignore. In that sense, the far right parties, just like the left parties such as the Green Party and its pro-environment, anti-nuclear, pro-civil rights portfolio, play an appropriately important role as the purveyor of new ideas that foments discussion and debate about real and substantive issues. The presence of minor parties creates a vibrant dialogue between the political center and the wings that Americans cannot even imagine, let alone benefit from. It reflects the fact that proportional representation inspires new parties and new coalitions to form in response to the issues of the day. It can be very responsive to the public mood, but it can sometimes feel like a roller coaster ride.

But the roller coaster, over time, usually finds its way back closer to the center of political equilibrium. The famous late 19th-century German statesman Otto von Bismarck reportedly said, “If you like laws and sausages, you should never watch either one being made.” We could say the same thing about government formation and multi-party democracies founded on the bedrock of proportional representation.

Misunderstandings of proportional representation

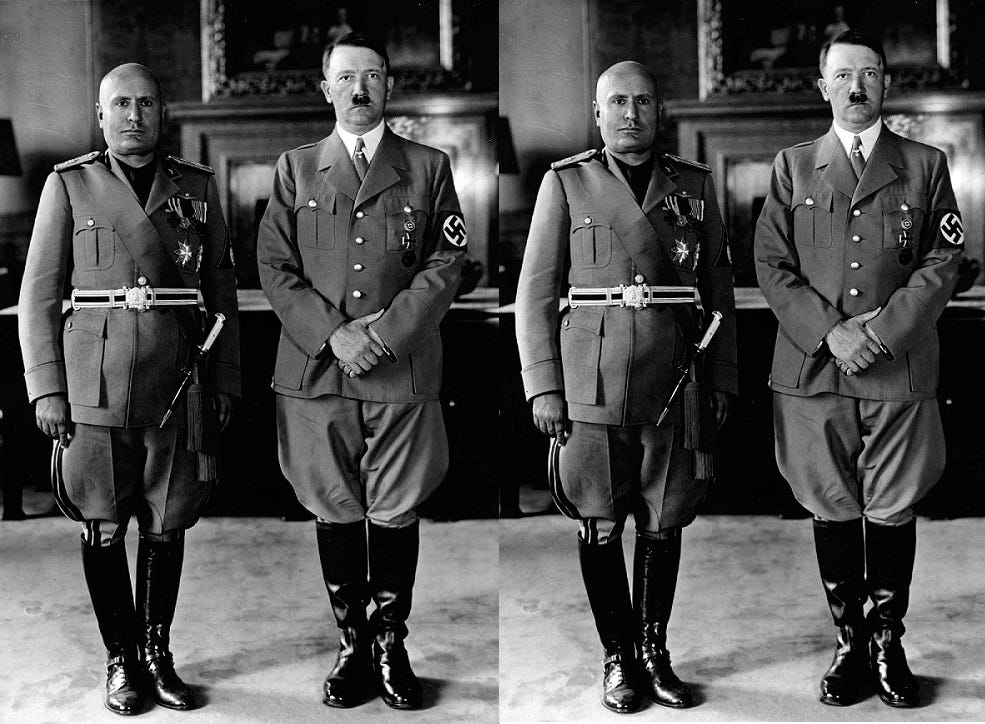

Some US critics contend that Germany’s use of a proportional representation electoral system in the early 1930s during the hapless Weimar Republic was responsible for bringing Adolf Hitler to power. When I posed this question to a leader of the conservative Christian Democratic Union in Germany, he just laughed. He dismissed such an idea as preposterous, citing numerous other aspects of the Weimar Republic that were far more significant in the rise of Nazism. In fact, some scholars contend that if the Weimar Republic had used a U.S.-style winner-take-all electoral system, its “sweep effect” would have magnified the electoral impact of the Nazi Party, causing them to win even more seats than they won under PR.

American pundits, critics and political scientists who say PR gives too much influence to extremists reveal how little they understand their own political system. They fail to recognize that in America’s winner-take-all system, small slices of the most zealous parts of the electorate (“the base”), combined with the least informed and most detached parts of the electorate (“swing voters”) acquire exaggerated power, determining which party wins the presidency, Senate and the House if they tilt the results in a handful of battleground states, such as Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania, or in a handful of swing House districts. In the Senate, forty-one filibustering Senators representing as little as 10 percent of the nation can stonewall legislation. The US is suffering from its own variant of the most cancerous form of minority rule.

Besides, PR systems have a fail-safe: they can handle political extremists by raising the “threshold of victory” (the percentage of the vote needed to win a seat) to a suitably high level that limits the extremists’ political impact as well as the number of parties in the legislature. Electoral systems designers like the researchers and political scientists at the Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance understand that with proportional systems you can establish different victory thresholds to fine-tune a democracy and make it as representative — or as exclusive — as it needs to be. Not enough US political scientists are familiar enough with the principles and practices of electoral system design.

Real fascism grabs for the power centers

What all of this points to is that fascism is not about which political party uses the most obnoxiously inflammatory rhetoric, or where a political party stands on the many political issues. It’s really about a political party’s relationship to power. And whether a political party figures out a way to gain a monopoly on that political power, either through violent means or by manipulating democracy itself.

Exhibit A is Hungary’s Viktor Orbán. If there is any tinpot leader that comes closest to this definition of fascism, it’s the former soccer star turned Magyar Prime Minister. But here’s the double irony – while Hungary does use a proportional representation system, it combines that with a US-style “winner take all” electoral system. And it’s actually the “winner take all” system that is allowing Orbán to use Hungarian democracy as a vehicle for amassing overwhelming power and wrecking democracy itself.

Orbán grossly manipulated his country’s winner-take-all districts. In elections earlier this year, Orbán’s party Fidesz won 54% of the popular vote yet turned that into 82% of the single-seat district races, and 67% of the seats overall. Orbán and his cronies changed electoral laws designed to cement his advantage for years to come, including increasing the percentage of winner-take-all districts from 46% of all seats to 53%, and giving the power to redistrict to his political party instead of an independent commission, which then rammed through a gerrymander on steroids.

Orbán’s soul mates in Poland pulled off a similar circus trick. In 2015, Poland used a “winner take all” method in 100 single-seat districts to elect the Senate. The Law and Justice Party received 40% of the popular vote yet ended up with 61 of the 100 seats. Now that’s a gerrymander!

And Italy’s far-right swing was aided by the same “winner take all” dynamics. Meloni’s coalition won 44% of the popular vote but like in Hungary won a head-spinning 82% of the seats elected by “winner take all” district seats. Due to that votes-to-seats distortion the right-wing took over with a whopping 59% of the legislative seats in the Chamber of Deputies. In fact, it’s in the “winner take all” districts where Meloni won her lopsided overall majority, allowing a minority of votes to win a solid majority of seats.

So it’s too simple to conclude that Europe is being overrun by goose-stepping, sieg heiling fascists. That viewpoint reflects a gross misunderstanding of Europe’s political landscape. Any political reading must recognize that electoral systems are powerful and their impacts profound. There is no clear evidence that proportional representation facilitates the election of right wing parties and candidates any more than left wing or centrist parties and candidates. It's designed to ensure that the broad range of public opinion has a seat at the table.

In the meantime, there's plenty of evidence that the US-style winner-take-all system has contributed to right wing victories and government majorities. Including in the United States itself. That's the exact opposite of what most Americans have been hearing from the “experts” for the last several decades.

Steven Hill @StevenHill1776