Faulty Textbooks: The Strip Mining of Anthony Downs’ "Economic Theory of Democracy"

One of the great political theorists of the second half of the 20th century had his work grossly misrepresented. I know, because he told me so.

Anthony Downs’ heralded Economic Theory of Democracy has long been a seminal work, often cited by political scientists and theorists since its 1957 publication. An economist, Downs used game theory and spatial equilibrium models to say some interesting things about competition and political stability in a winner-take-all, two-party system. His work, which built upon the thinking of his predecessors mathematician Harold Hotelling and Nobel Prize-winning economist Kenneth Arrow, provided one of the most influential theories invoked for decades to legitimate the alleged political centrism and moderation resulting from the American political system. Testifying to its enduring clout, a search of Downs’ Economic Theory of Democracy in a search engine turns up 111 million entries, more than the Federalist Papers.

Yet as we observe the deep rifts of polarization and toxic partisanship that plague American politics today, we can’t help but wonder: did Anthony Downs’s work on rational choice politics somehow get it wrong?

The answer, as we will see, is no: Downs got it exactly right. But unfortunately a couple generations of political scientists, politicians, pundits, judges and other nationalist ideologues misinterpreted Downs, strip mining the fullness of his beautiful theory in service to a political agenda. Downs himself was aware of this, as he told me when I met the great man following the publication of my book Fixing Elections: the Failure of America’s Winner Take All Politics. In that book I strongly criticized these neo-Downsians, and Downs complimented me on my smack-down (more on that later).

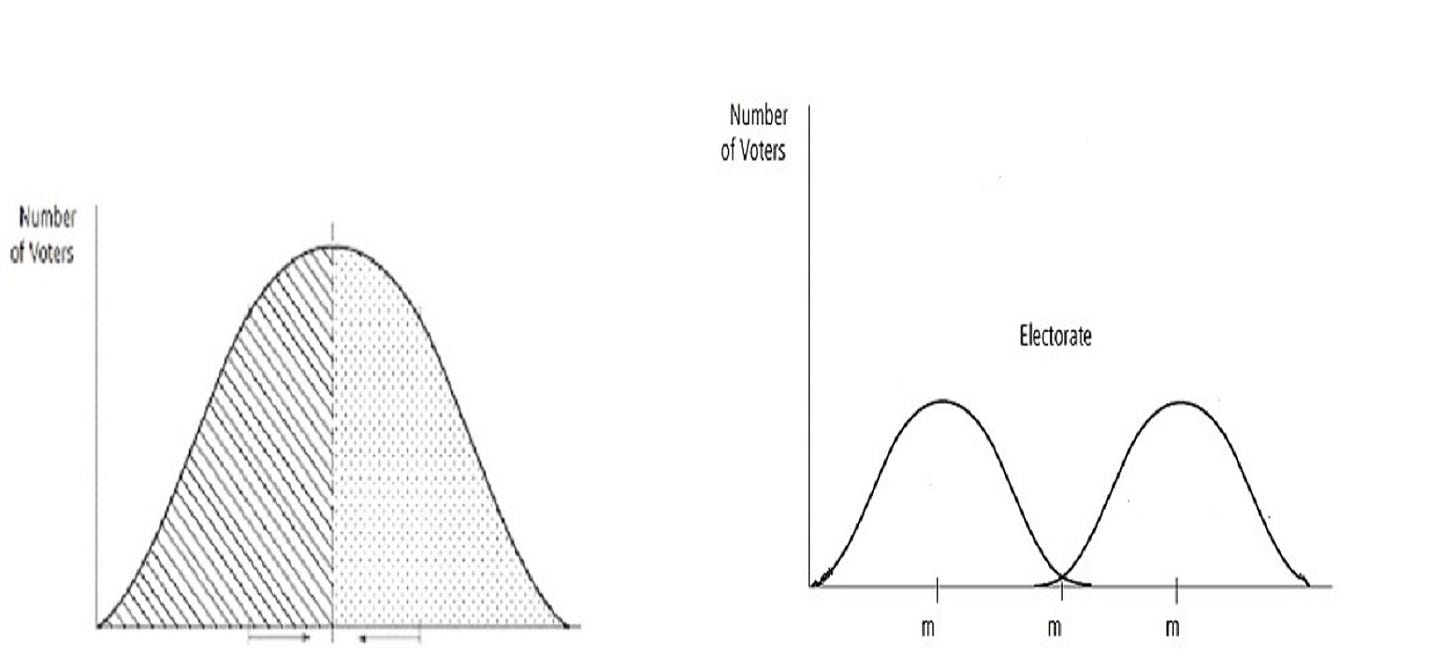

According to the core argument of Downs’s theory, a two-choice/two-party system will cause both parties to move toward the two points on the political spectrum where the most numbers of voters reside, in terms of their political beliefs. Parties are vote-maximizing machines, and they sniff out voters’ views like bloodhounds chasing a prison escapee. Of particular interest to Downs were two specific voter distributions: 1) when most voters are amassed at the political center, i.e. the median-middle (illustrated by a one-humped curve), and 2) when voters are polarized into two ideological camps, one to the right of the center and the other to the left (a two-humped curve, see the illustrations below).

In the first instance, Downs built on the previous theoretical work of Hotelling’s “ice cream vendors on the beach” model. If there are two ice cream vendors, each will position their ice cream stand in the middle of the beach, right next to each other, to maximize the number of customers that each of them is spatially closest to, when compared to their competition.

Downs posited that, given a voter distribution where most voters are amassed at the middle of any particular political spectrum, the two political parties will tend to converge in the center where most of the electorate is concentrated. Both parties will tend to adopt the views of what is called the “median” voter -- the voter closest to the middle of the ideological spectrum. That’s because the strategic incentives for the two parties, and the rational choices for voters picking candidates and parties in a limited two-choice field, act together to provide victories for the party that is closest to the median. A party that fails to converge to the middle can always be defeated by a party that does (with one important addendum: that fear of losing their own extremist voters would keep the two parties from drifting completely to the median-center and “becoming identical”).

Thus, according to this Downsian model, whenever Democrats and Republicans appear to overlap in their political posturings, that actually is rational behavior by politicians trying to maximize votes and win elections in a two-choice field. Given a “one-humped” distribution of voters amassed in the middle of the political spectrum, if either of the two political parties stray too far toward the margins, they will yield more of the political turf to their opponent. So both parties stride toward the middle.

This reality has given rise to a classic political strategy: in the primaries run to your base, but in the general election run to the center -- different elections with different median voters, with primaries determined by median voters considerably more partisan than in a general election. Certainly the triangulation of Bill Clinton in 1992 and 1996, the “compassionate conservative” version of George W. Bush in 2000, Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” and Hillary Clinton’s “It Takes a Village” in 2016, and Joe Biden’s “Restore the Soul of the Nation” in 2020 attempted to utilize such a strategy, and the Downsian spatial equilibrium model purports to show us why.

Downs’ work was enormously influential over the ensuing decades. His rational choice formulation of politics permeated through the academy, even the culture at-large. The pandemonium known as politics had been modeled and reduced to “natural law,” just like economics or physics, in a way that seemed to make sense out of the chaos. It is hardly possible to overstate the influence of Downsian theory, cited and re-cited by political scientists, judges, journalists, pundits, politicians and editors.

Downs’s two-hump exemption

But like the One Ring of Power that was misplaced and forgotten for too long, everyone seemed to forget that Downs had proposed an important exception: what if, he asked, the distribution of voters is not humped in the middle of the ideological spatial market? What if instead the electorate is polarized? In that case, Downs showed, the two parties will “diverge toward the extremes rather than converge on the center. Each party gains more votes by moving toward a radical position than it loses in the center.” When the electorate is polarized, Downs’ model portrayed the distribution of voters as two-humps, equal in size, like a Bactrian camel’s back.

In such a situation, Downs goes on to predict that “regardless of which party is in office, half the electorate always feels that the other half is imposing policies upon it that are strongly repugnant to it.” But in addition, Downs wrote "In this situation, if one party keeps getting reelected, the disgruntled supporters of the other party will probably revolt; whereas if the two parties alternate in office, social chaos occurs, because government policy keeps changing from one extreme to the other.” Thus, Downs concluded, the two party system “does not lead to effective, stable government when the electorate is polarized.” These predictions look presciently familiar when observing US politics today, as many diehard supporters of both the Democrats and Republicans are convinced that the other side is tantamount to evil.

In the ensuing six decades following Downs’ pivotal work, political scientists, editors, pundits, politicos and academic researchers selectively strip mined Downs for their own purposes. These neo-Downsians ignored those parts of the Downs model that apparently did not fit in with their preferred vision of America as a nicely-organized, centrist, single-humped electorate. Thus, Downs’ formulation of what happens to a democracy when the electorate is polarized into two voter distribution humps somehow was left on the cutting room floor.

What remained was a half-baked simulacrum of the Downs theory, and the two-party system transmogrified in many minds into a proxy for moderate, majoritarian, centrist government. Down’s median voter acquired a reputation as a political moderate. And the policy passed by that government was presumed to be preferred by a majority of voters.

To catch a glimpse of the type of dross that trickled down into mainstream culture and education, here is a passage from one encyclopedia: “Majority or plural methods of voting are most likely to be acceptable in relatively stable political cultures. In such cultures, fluctuations in electoral support, given to one party or another from one election to the next, reduce polarization and make for political centrism.” One political scientist wrote that our “exceedingly fluid two-party system” is built upon “tenuous compromises” between ideological factions and special interests “which are forced at every turn to moderate their claims.”

Even Supreme Court justices like Antonin Scalia and Sandra Day O’Connor, straining in some of their opinions to sound erudite, fell back on unsubstantiated neo-Downsian characterizations. Justice O’Connor’s concurring opinion in Davis v. Bandemer (1986), joined by Chief Justice Warren Burger and Justice William Rehnquist, declared “There can be little doubt that the emergence of a strong and stable two-party system in this country has contributed enormously to sound and effective government.” Scalia, in his dissenting opinion in Rutan v. Republican Party (1990), joined by Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justices O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy, wrote about the differences between two political parties being moderated by Downsian-like incentives “as each has a relatively greater interest in appealing to a majority of the electorate and a relatively lesser interest in furthering philosophies or programs that are far from the mainstream. The stabilizing effects of such a [two party] system are obvious.”

For decades this conventional wisdom was proclaimed across the land: that centrist, moderate government had been more or less achieved, at least theoretically according to the neo-Downsians, and unsurprisingly it looked quite a lot like two-party government in the United States. Like the Chicago School of economics had cemented its rational choice orthodoxy into the world of supply and demand and inflation and growth, this neo-Downsian orthodoxy came to dominate political science and popular thinking in the United States for the past 60 years.

But this was certainly a misreading of Downs. Downs had postulated an important exception: except when a polarized electorate leads to a more difficult brand of democracy. For Downs, the behavior of vote-maximizing parties was determined by the distribution of voters, not the other way around. One of the strengths of Down’s model was that it was flexible, and examined the reaction of political parties pursuing voters from different voter distributions. Yet an unsubstantiated assumption had crept into the neo-Downsians’ revisions of the model: like a kind of political conveyor belt, the two-choice dynamic was presumed to drag both parties inevitably to centrist positions of moderation, leading to a politically centrist, moderate, majoritarian government -- regardless of the distribution of voters.

The “polarized electorate” exception inexplicably had been dropped from the neo-Downsian canon, but politics in the real world is not always cooperative or kind to those who try to bend theory to their will. The outstanding question was: which distribution of voters was applicable to American politics? The “one-humped” majority of voters amassed around the ideological median-middle? Or a “two-humped” polarized distribution of voters? Or perhaps a distribution somewhere in between the two extremes, or one that fluctuated between the two extremes over time? There was a one-hump vs. two-hump uncertainty to figure out. Only after answering that question could anyone begin to speculate whether the politics of policy-making would lead to moderation and centrism, or polarization and paralysis.

One hump vs. two: median votes are not neutral

Like many other keen observers, I remember when USA Today's red versus blue America map first was published following the 2000 presidential election. For many political observers -- particularly those more soberly contemplating the Downsian model -- that map of the national vote caused the hair on our necks to raise, precisely because of what it conveyed: a national two-hump distribution of polarized voters, cleaved along starkly regional lines. It was like some sort of two-humped Godzilla monster, rising up out of the sea.

Whenever the nexus of partisanship and geography have smashed together in US history, the outcome usually has been explosive. Alarmingly, the same two-humped Godzilla appears when analyzing congressional elections. The vast majority of U.S. House races are completely noncompetitive, with 90% won by predictable 10 point margins, and three quarters won by landslides. That’s because these districts are lopsided, one-party fiefdoms for either the Democrats or Republicans, and not usually as a result of redistricting abuses. Instead, the regional partisan demographics, in which Democrats dominate in urban areas and Republicans in rural, exurbs and many suburban areas, determine electoral outcomes in the vast majority of U.S. House contests.

Indeed, nine out of 10 districts are so partisanly skewed that the winner is actually determined in the primary of the party that dominates that district, where the median voter is partisan and anything but neutral. In state legislatures it’s even worse, with so many safe seats in most states that typically 40% of the legislative races are uncontested by one of the two major parties. In actual fact, demography has become destiny in most legislative elections in the United States. That is, a two-humped demography, based on regional geographic polarization.

If that is the case, then by definition in most of these elections the median voter is not neutral, and not an undecided or swing voter. Instead, the median voter in each district is a partisan voter. A number of studies have found a strong link between vote shares and partisan legislative behavior: the safer the seat, the more partisan the legislator. One study found that, “because most congressional districts heavily favor one party for long periods…in these cases, no convergence toward the political center is necessary or expected… there are very few conditions where party convergence will occur.”

All other things being equal, a legislator in a safe district is more likely to vote positions corresponding to the party’s wings, not the center, compared to a legislator from a competitive district. It is only as vote shares decrease i.e. as races became more competitive -- with very few of such contests every year -- that representatives’ positions gravitate toward the political center. Harvard political scientist David King captured the reality: “Political scientists may instinctively suspect that polarization is an irrational strategy for party elites running the parties. The party locating its policy positions closest to the preferences of the median voter is supposed to get the most votes, or so we have been taught. With that model in mind, it makes little sense to allow one’s own party to become extreme. But that is precisely what has been happening.”

Thus, the logic of party convergence collides with the unmistakable party wars. The overwhelming numbers of safe seats has produced a lack of accountability that in turn has produced “the rise of the ideologue.”

Yet neo-Downsian rational choice models based exclusively on a single-hump voter distribution had predicted the opposite pattern. According to the neo-Downsians, the “drive to the center,” toward median voters -- toward moderate voters -- was a proxy for a two-choice, winner-take-all system that, on the whole, produced centrist political winners and majoritarian governments of moderation.

One conclusion was glaring: for the past four and a half decades since the mid-70s at least, Downs’s two-humped model had been slowly becoming the more accurate descriptor for most U.S. House races, with one partisan hump larger than the other, usually drastically so, depending on the district (i.e. in landslide safe-seat districts, which typify three-quarters of U.S. House races). Rather than having strong incentives for centrist politics, we have a system that favors partisan politics: politicians are rewarded for staking out extreme positions because most owe their seats to ideologically skewed electorates.

Thus, just as with the national vote revealed by the USA Today map of the 2000 presidential election, Downs’ two-humped model had become the operative voter distribution pattern for most congressional races. Given the partisan shape of regional demographics in Red versus Blue America, combined with the dynamics of winner-take-all districts where the highest vote-getter wins everything and every other vote-getter wins nothing, it should not be surprising that the U.S. House has split into two polarized camps—a more solidly liberal Democratic Party and a more solidly right-wing Republican Party, like two tectonic plates drifting in opposite directions, with a dwindling number of moderates between them trying desperately to bridge the gap.

Downs’ original model, which included the possibility of a one-humped or two-humped voter distribution, it turns out, had been exactly right. But those who strip mined the fullness of Downs’ theory had thrown their weight around for decades. Over time, their half-baked version of their mentor’s work acquired a vast degree of influence. Neo-Downsianism rose to the level of political dogma, indeed it became a kind of priestly orthodoxy. The dogma trickled down to popular culture; it was championed in the mainstream press, inserted into encyclopedias, taught in the universities and civics classes with a kind of nationalist pride, with the Wall Street Journal and New York Times acting as high priests of the canon. During the height of the Cold War, America’s centrism was part of our “soft power” on the world’s stage.

In the end, Downs’ clever and provocative model had transmogrified into a stultifying stereotype: everyone knew, it seemed, that the kind of government and winner-take-all political system used by the United States was the best in the world because it led to effective, centrist, stable, majoritarian government. Those who still swear by winner-take-all’s alleged centrism would have us believe that today we can have a U.S. House of Representatives that is populated by more radical conservatives and unabashed liberals and fewer and fewer moderates, and yet somehow this two-humped Godzilla monster will find its way to enact centrist, moderate policy. It would be a miracle if such were the case. Unfortunately, it is not.

This is a repudiation of neo-Downsian dogma. A great deal of empirical evidence and real-world behavior contradict any spatial voter distribution models that predict a two-party winner-take-all system will produce moderate, centrist or majoritarian policy. As our politics have fragmented and polarized, the fuller version of Downs’ model including the two-humped “polarized electorate” exception would have predicted such fragmentation and the distorted policy that results.

“I am not a Downsian”

Following the publication of my book Fixing Elections, I gave a lecture at the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC). In my talk, I outlined my analysis of the neo-Downsians’ revisionism. Afterward, a gentle, slow-moving elderly-looking gentleman made his way to the speaker’s lectern with a copy of my book Fixing Elections in hand. He patiently waited his turn, as I spoke with several of the other audience members gathered round. Finally, as most of the audience trickled away, he humbly introduced himself.

“Um, my name is Tony Downs, and you made some comments on my book, Economic Theory of…” He didn’t need to say more, I recognized him from his younger photos. My heart raced and my pulse quickened. It was an Annie Hall moment, when a know-it-all moviegoer, a Columbia University professor no less, was expounding to anyone within earshot about the work of Marshall McLuhan and suddenly was confronted by McLuhan himself.

Gulp. I braced for a rebuttal.

“I want to congratulate you,” said this protean figure, “because you really got it right. You understand my point about the two-hump voter distribution.” He went on to say how dismaying it had been for him for so many years to see his work mischaracterized and erroneously cited by numerous political scientists to legitimize their academic work and politicize his work in a way that was the opposite of what he had intended. Despite his emeritus status and gravitas, and his position then as an honored fellow at PPIC, Tony (as he liked to be called) was just as congenial and humble as a great man could be. He showed a good humor about it all, even though it had become necessary for him to distance himself from these misinterpretations of his work. I half imagined a frustrated Tony Downs seeing fit to declare, "I am not a Downsian!”

That chance meeting with one of the great political theorists of the second half of the 20th century was a personal thrill that validated my own work. At this point, it’s pretty hard to argue that centrist, moderate, majoritarian government is guaranteed by a geographic-based two-choice system. In fact, under winner-take-all’s paradigm, it is somewhat of a crapshoot. And observations of national politics in recent years bear this out. Each day that Americans suffer under the instability of our geographic-based, two-choice, winner take all political system makes it all the more urgent that the US transition to a democracy established on the bedrock of proportional representation.

Steven Hill @StevenHill1776

I am wondering if our metaphor of the center and moderate gets in the way here. I rather see the center not a quiet separate space but as a dynamic tension. Not between extremes but understanding, challenging, and even integrating those so called extremes which probably also is a bad metaphor. Yes, the three party system that calls for coalition building (e.g. Canada, Britain) could be more helpful and inclusive. As well as a ranking system of voting. However, as an old but still active community organizer, I support building public space in the neighborhoods and workplaces in order to maintain the tensions productively. Our polarization is certainly a matter to be studied by evolutionary and group psychology. But I think the root of it is that many people (including white, rural, conservative people) have been left behind economically (in terms of living standards) as well as politically (in terms of respect). Could we achieve democracy more by dealing with equality--so that we deal with interests over identity?

By today's standards, your article might be considered lengthy, but it is well worth the time to read it all. I suspect that the two humps will continue to drift farther apart until a third party creates a central hump. However, as long as single choice plurality voting is prevalent, the central hump will be of minimal amplitude.