German elections headed for a crash? Need RCV?

With three parties potentially missing the 5% victory threshold, why don’t List PR systems allow voters to rank more than one party?

[Dear DemocracySOS readers, if you are enjoying DSOS content, here is a link to the $5 subscription page. Thanks for throwing a few tuppence into the hat!].

Germany is about to vote in a national election on February 23, with many of the same issues playing out there that thundered in the US presidential and congressional elections last November – high prices, pressures from immigration and the rise of populist extremists.

But a key difference between the German and US elections is the electoral system and the parliamentary structure of government. In Germany, its proportional representation (PR) system fosters multi-party representation, with anywhere from 4 to 8 viable parties campaigning to win seats in the Bundestag. While German democracy is a colorful peacock of partisan diversity, in the US we are stuck with the same old humdrum two-toned turkey, as Democrats and Republicans ineptly oversee the only wealthy nation in the world that has still not figured out how to provide healthcare to all of its citizens.

There’s no question that, generally speaking, nations that use PR electoral systems tend to do a better job of providing for its people and fostering a higher quality of life, as documented by numerous political scientists such as Arend Lijphart and G. Bingham Powell. PR democracies are far more representative of the diverse political perspectives in society, and therefore are more reflective of a society-wide consensus that has not been possible in the US.

But that doesn’t mean that proportional representation methods are perfect, or don’t have some of their own peculiarities. One of those is about to play out in the German elections.

The “wasted vote” problem with some PR methods

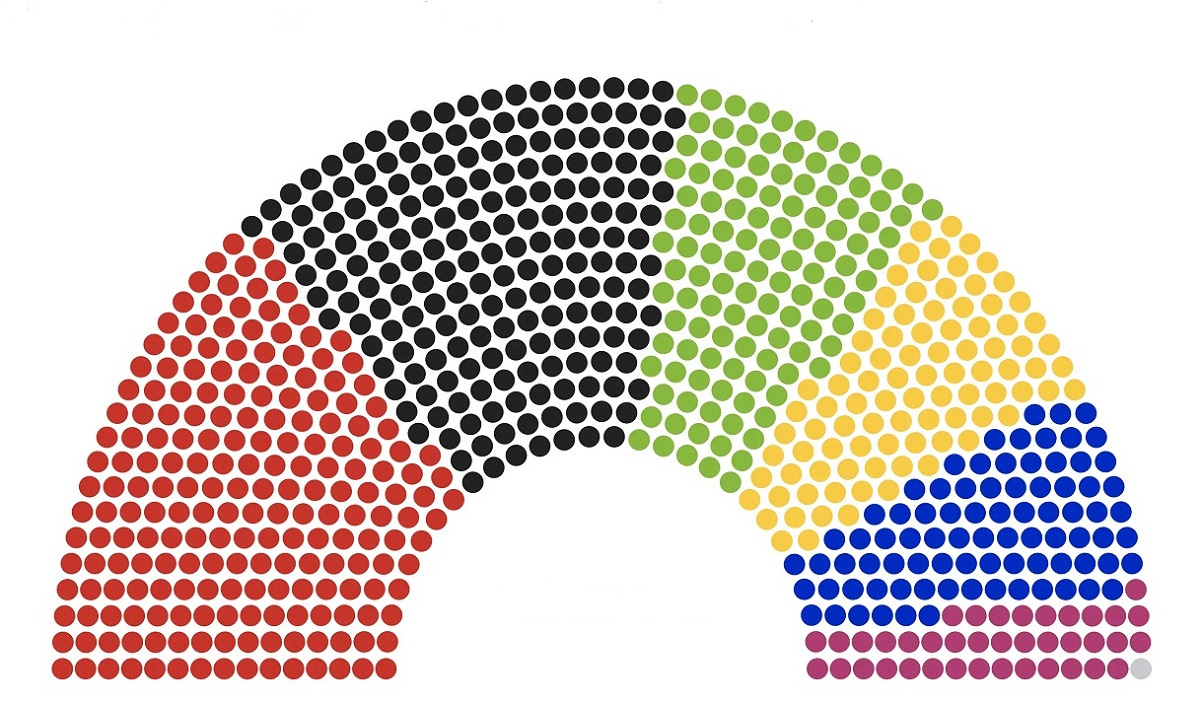

The governing center-left Social Democratic Party is about to be unseated by the center-right Christian Democratic Party for all the reasons Kamala Harris lost to Donald Trump, plus a few more. So the question is not who will be the next chancellor and lead the government in Germany’s parliamentary system, but rather which parties will govern in coalition with the Christian Democrats. Depending on a shift of only one or two percentage points for several of the smaller parties, the coalition could look very different.

In Germany’s “mixed member” proportional system (called MMP for short), a political party needs to win 5% of the popular vote in the multi-seat districts in order to “cross the threshold” and be awarded its fair share of the 630 seats in the Bundestag (also, a party can enter parliament by winning three of the single-seat district seats that are elected, along with the List PR seats, in Germany’s mixed system). Generally in PR democracies, a party that wins 10%, 18% or 26% of the popular votes wins 10%, 18% or 26% of the parliamentary seats, whereas in the US "winner take all" system, such a low percentage of the popular vote usually wins nothing.

Three of the smaller German political parties, the Free Democratic Party, Die Linke (the Left Party) and the Alliance Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW), are hovering right around the 5% level and in danger of getting shut out of parliament. The first two parties are long-standing players on the German landscape, and have been winning seats in the Bundestag for decades. BSW is a new party led by a well-known leader of Die Linke, Sahra Wagenknecht, who splintered off and formed her own party (which is much easier to do in a PR system than in the US-style “winner take all” system).

If all three of these parties fail to cross the threshold, then a couple of undesirable impacts will occur.

First, upwards of 15% of German voters will have wasted their votes. If these voters had known their party was not going to win any seats, they might have voted for one of the four larger parties that are certain to win seats. But unfortunately, without a magic crystal ball no one has advance perfect knowledge. So many German voters are about to waste their votes on an unelected political party.

Of course, that happens in American elections all the time. Germany’s MMP system (which combines List PR with single-seat districts) doesn’t waste nearly as many votes as America’s “winner take” electoral system. In the US, for each district seat election, 49.9% of voters can waste their vote on a losing candidate. If there are three or more candidates, an even higher percentage of voters could cast votes for losers. In the 2024 presidential election, in which Donald Trump won with 49.8% of the popular vote, a majority of voters wasted their votes on losing candidates.

Some members of the US Congress, as well as governors and other elected officials, have won their seats with 32 to 40% of the vote (most particularly in party primaries in lopsided partisan districts), which means up to two-thirds of voters wasted their votes on unelectable candidates. And supporters of small parties like the Libertarians or Greens have no chance at all to elect their candidates and party.

While the “wasted vote” situation is not as extreme in PR democracies like Germany, nevertheless any voters considering a vote for their favorite small party still have to consider voting strategically by casting their vote for a party with a better chance of winning. These voters are still stuck calculating whether to cast a vote for the “lesser of two evils.”

Wasted votes can contribute to distortions in coalition-building

The second undesirable impact that can happen in List PR elections as a result of wasted votes, especially when combined with a parliamentary government like Germany's, is in the coalition-building process. Specifically, whether or not the FDP, Die Linke and BSW pass the threshold could significantly impact which parties are included in the governing majority coalition.

For example, if the FDP, Die Linke and BSW all win less than the 5% threshold and end up with no seats, the four winning parties would be awarded more seats, even higher than their share of the popular vote. That would especially benefit the frontrunner, the Christian Democratic Party, who currently are polling at around 30% (in combination with its smaller sister party in Bavaria, the Christian Social Union). But that vote share would win about 37% of the seats, allowing the CDU/CSU to form a government majority with just one additional coalition partner, either the SPD or the Greens.

However, if the FDP, BSW and Die Linke all surpass the victory threshold, the CDU/CSU's seat share would shrink to 30%, and that would mean it would have to form a three-party coalition. That becomes more challenging to juggle the demands of two coalition partners, since the partners might make for strange bedfellows. That’s what happened in the current SPD-led coalition with the FDP and the Greens, and when that unstable coalition finally fell apart from internal tensions and infighting, the voting public blamed the coalition partners, which boosted the CDU’s electoral fortunes in this election.

Generally I like the simplicity of most List PR systems, but “wasted votes” is one of the drawbacks of this system, compared to another PR system like single transferable vote/proportional ranked choice voting. In a close election in which the outcome of either vote shares or coalition partners (or both) is decided on the margins, and when a number of small parties fail to reach the electoral threshold, those voters have essentially wasted their votes. And those wasted votes can impact the coalition formation.

Past results tell the story

This dynamic already manifested in the 2013 federal elections in Germany, when 34 political parties competed but only five parties crossed the 5% threshold and won seats. Votes for the other 29 parties were wasted, resulting in 15.7 percent of the List votes going to losing parties. In Germany’s more recent 2021 elections, approximately 7.5 percent of the List vote went to parties that fell short of five percent.

An even bigger impact can be seen in the Israeli election of 2022. There were 40 political parties and 10 of them crossed the 3.25% threshold necessary to win seats. With votes for the other 30 parties being wasted, it meant that 8.5 percent of the vote did not count toward electing a party. Because nearly 300,000 anti-Netanyahu votes were wasted on parties that did not reach the victory threshold and win representation, prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s extreme right-wing coalition of allies was able to barely squeak out a majority of legislative seats despite his religion-dominated coalition winning only 48 percent of the popular vote. Given the corruption and criminality of Netanyahu personally, as well as the war crimes and genocide perpetrated by his government according to everyone from the International Criminal Court to the United Nations and Israeli historians, these “wasted vote” dynamics have had tragic consequences.

Wasted votes in List PR elections are fairly common. In Italy’s recent election, 11.2 percent of the List vote went to losing parties; in the Czech Republic 19.9 percent, Slovenia 24 percent, Slovakia 28.4 percent, Latvia 28 percent, New Zealand 7.8 percent. However elections in other List PR countries have resulted in much lower percentages of wasted votes, so this is not always a hard and fast rule. But when it happens in a close election, it can affect not only the number of voters who waste their votes on losers but also the outcome of which party finishes first, and the formation of the majority coalition government.

The solution: ranked ballots to the rescue

If Germany or other List PR democracies used ranked ballots, that would greatly reduce the number of wasted votes and increase the proportionality of the elections. Voters could be allowed the option of ranking up to three parties, and if their vote for their favorite party cannot help that party cross the victory threshold, their vote would pass on to their next-ranked party choice. So if a German voter ranked Die Linke first, and Die Linke failed to cross the 5% threshold, that voter’s vote would not be lost. She could rank another party that is somewhat ideologically aligned with her views, such as the Green Party or the SPD, as her second choice. Her vote would then count for that party.

The ranked ballots would ensure that votes for parties that don’t have enough support to reach the victory threshold are not wasted – voters’ rankings would be used to re-allocate votes to the parties still in the race, using every voter’s ballot efficiently. The ranked ballots would maximize the number of voters who actually cast a vote that helps elect a party, and that in turn would increase representative proportionality, i.e. it would better ensure that parties win the number of seats that reflects their true popularity.

In the most recent Ireland elections using ranked ballots, only one percent of votes were cast for parties who failed to win any seats and were therefore wasted. The use of transferable ranked ballots is why proportional ranked choice voting can be used successfully in a district magnitude of 3 to 7 seats (and a victory threshold of 12.5 to 25 percent), a design that is used in the Republic of Ireland and Australia. Few votes are thrown away. In contrast, a List system with a low number of district seats would likely result in substantially large numbers of wasted votes and a degree of instability in election outcomes and coalition formation.

Ranked ballots are one of the wonders of modern representative democracy. Allowing voters to rank their ballots is an unequivocal democratic improvement, and it's puzzling why they aren’t incorporated into List systems.

Some people believe ranked ballots are complicated, or make the voting process more complicated, but that’s just an unjustifiable disparagement of allegedly "dumb" voters. Millions of voters in the US, as well as millions more in Australia, Ireland and other places, use ranked ballots and handle the task of ranking candidates as easily as they handle the task of ranking their favorite flavors of ice cream or movies. In exit polls from New York City's first ranked choice voting elections, over 90% of Black, Latino, and Asian voters found their RCV ballot "simple to complete."

There actually is a version of ranked choice voting that can be applied to the ranking of parties instead of candidates, called Spare Voting (also sometimes known as “two-choice MMP”). The Spare Vote is intended to encourage voters to vote more honestly for their favorite party and not worry about “lesser evils” dynamics. Democratic nations using List PR methods would be wise to incorporate ranked ballots into their elections. Doing so would reduce wasted votes, increase representative proportionality, and better ensure coalition congruence. A List/RCV hybrid would empower voters with more electoral choice, and reduce fears over unintended consequences of wasted votes.

With so many people today having gone sour on government and democracy, adding ranked ballots to List PR would liberate voters and perhaps help some of them feel better about government again.

Steven Hill @StevenHill1776.bsky.social @StevenHill1776

Thanks for sharing. Great thoughts. I wonder if another benefit of ranking parties might be that rather than the party winning the largest plurality of seats getting the first crack at forming a coalition, that privilege would go to the IRV majority winning party.

There is quite a lot of talk about "wasted votes" here. I think disambiguation would be helpful. https://luckorcunning.blogspot.com/2024/03/can-wasted-vote-really-mean-all-these.html