Here's how to DOUBLE voter turnout

California, Arizona, and Nevada have shifted to even-year elections, boosting turnout and saving money—with lessons for other states.

[For this article, DemocracySOS welcomes Alan Durning as a guest contributor. Alan is founder and executive director of Sightline Institute, which is an independent, nonprofit think tank providing leading original analysis on housing, democracy, forests, and energy policy in the Pacific Northwest, Alaska, British Columbia, and beyond.]

Many election reforms—gerrymandering bans, ranked choice voting, proportional representation—are controversial. Winning them is a daunting prospect. But one is snoozingly uncontroversial among US voters, even while it boosts turnout more than any other change scholars have studied.

That reform is election consolidation: rescheduling local elections to occur with national and state elections in even years (often referred to as “on-cycle elections”). Nationwide, researchers have found that local voter turnout generally doubles when elections move from off-cycle to on-cycle contests. That’s a remarkable finding, considering that get-out-the-vote and registration drives are lucky if they boost participation by a percentage point or two. That’s why, as my organization Sightline Institute has argued time and again, election consolidation to even years is the best-kept secret of reforms, the one voter turnout reform that rules them all.

It’s also amazingly popular. When an election consolidation plan comes before voters, it usually passes by a wide margin and with little debate. To voters, synchronizing elections is a no-brainer. There should be one general Election Day, they believe, and it should be the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November of even years. The primary election should precede it by a few months.

Unfortunately, legislators do not always agree. Most state bills to put local elections “on cycle” with national ones quickly die, with little active support or debate. And in many states, state legislatures have not only failed to consolidate elections themselves, they have also barred cities from doing it on their own. They require cities to hold their elections “off cycle” on strange dates or in odd years. Consequently, local voters are stuck with too many elections; local leaders are chosen by small, unrepresentative electorates; and local budgets bleed from churning through unnecessary ballot handling.

Is change possible? Is there a politically realistic path to election consolidation? Yes, there is. Three states – California, Arizona and Nevada – have blazed the trail in recent decades. It starts with mild reforms at the state level that merely allow cities an option to consolidate elections. It moves next to ballot measures in multiple cities. And then it returns to state legislatures that mandate near-universal use.

ELECTORAL WINNING STREAK

For the public, election consolidation sells itself, like ice cream on a summer beach. Citizens want to vote less often. They’d rather fill out one long ballot all at once than two or three short ballots on different days. That’s why on almost every occasion when voters have considered consolidating elections, they have voted “yes” by large—sometimes, staggering—margins.

In November 2022, voters in 11 cities and one county considered election consolidation proposals for some or all city offices and passed every single one of them, usually by landslides. These cities included St. Petersburg, Florida by 70 percent, San Francisco by 71 percent, Long Beach by 75 percent, Fort Collins, Colorado, by 76 percent, San Jose by 55 percent, King County, Washington (which encompasses Seattle) by almost 70 percent, and others.

Previously, some 77 percent of voters in the city of Los Angeles approved election consolidation, as did 73 percent of voters in Phoenix, 90 percent of voters in Scottsdale, Arizona, and 66 percent of voters in Austin, Texas. This winning streak is almost unbroken because voters across the political spectrum like their elections rare.

LEGISLATIVE LOSING STREAK

If supported by the public, though, election consolidation is few people’s priority. Most think of it as common-sense but unimportant. No politician becomes a hero by championing the rescheduling of elections, and in fact, powerful interests sometimes oppose it.

Low-turnout elections skew toward “reliable voters” – those who consistently vote – and tend above all to be voters who are older, whiter, somewhat more educated, and homeowners. Some researchers have suggested that off-cycle elections also favor motivated and organized constituencies. Local elected officials themselves often oppose reform. They got elected with a certain set of voters. From their perspective, why mess with success? And local elected officials tend to have close ties with the state legislators who write the laws governing when localities hold elections.

The net effect of this combination of forces is inertia: in the absence of public pressure, the status quo continues. Most legislative proposals die. Sarah Anzia, a professor at UC Berkeley, found 219 bills in US state legislatures between 2001 and 2011 that promised to consolidate elections. Some 88 percent of them failed. Of the 25 bills that passed, almost all were weak or optional plans.

THREE WINS, ONE LESSON

Since the period of Professor Anzia’s study ended in 2011, Arizona, California, and Nevada have passed new laws that require almost all cities to move elections to November of even years. In each case, local action started the ball rolling, and a mild state reform came before a stronger one.

How California got on-cycle elections

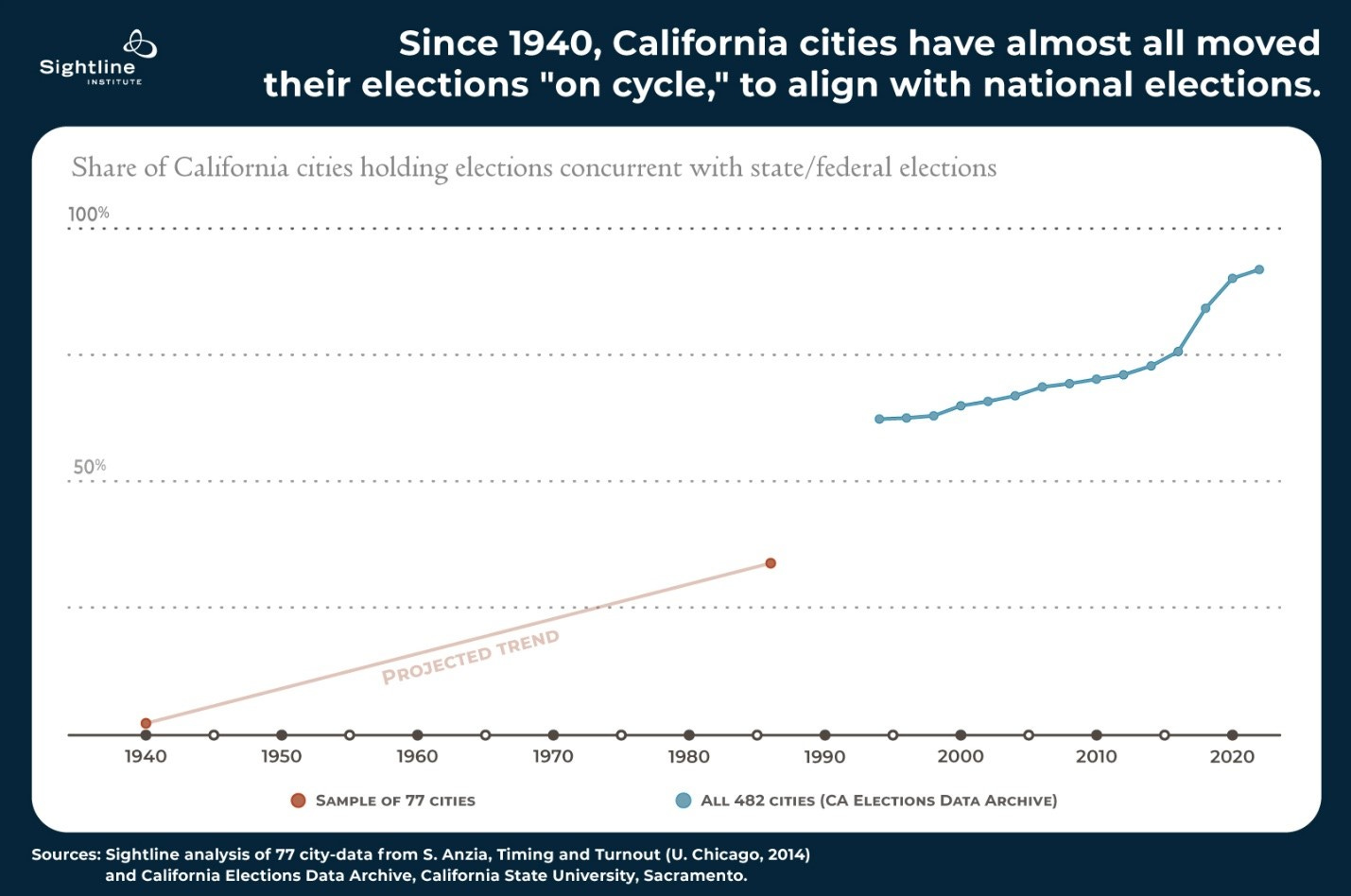

In California, as of 1940, a sample of 77 cities studied by Professor Anzia (p. 75) showed that all but 4 percent conducted their elections out of sync with the federal government, as was normal for the time. A trickle of consolidations started among “charter cities,” those big enough to have home rule city charters. In 1981, the state legislature allowed cities without their own charters to join the trickle, and by 1986, some 34 percent of the cities in Dr. Anzia’s sample had consolidated elections.

Election consolidation slowly picked up speed. By 1995, 62 percent of the Golden State’s 482 cities, about half the state’s urban population, had on-cycle elections. In 2015, the city of Los Angeles migrated to on-cycle elections by popular vote. The final push came that same year from the state legislature, which passed a law requiring all localities with low voter turnout to move to on-cycle elections (in the law, “low turnout” was defined as being 25% lower than that locality’s average for statewide elections). Earlier, cities might have objected, but by then, three-quarters of cities had already converted. The remainder were no longer much of a power bloc, and their neighbors were demonstrating again and again that consolidated elections saved money and boosted participation in democracy.

Quickly, local authorities rescheduled their elections, including large cities like San Francisco and San Jose. The new additions will push the share of California cities to well above 90 percent. All but one of the state’s largest 20 cities now hold their elections on cycle.

How Arizona and Nevada got on-cycle elections

In California, local action led to state action, which led to more local action, which led to more state action. In neighboring Arizona and Nevada, a similar pattern emerged. In 2000, the Arizona legislature lifted a prior ban on local elections in even-year Novembers, and a few cities began switching. In 2012, the Arizona legislature passed a law (HB 2826) to push remaining local elections to November of even years, and by 2018, most Arizona cities had complied, including the state’s 500-pound gorilla Phoenix, which is home to more than a fifth of Arizonans. Recent court rulings have exempted charter cities, but the rulings are largely moot since nearly all Arizona cities now run consolidated elections.

The story in Nevada has been similar: every city there voted off cycle before 2001, but in 2011, the legislature let charter cities make the switch without going through the nettlesome process of amending their charters. By 2019, 12 of the state’s 19 main cities were already on cycle or in the process of transitioning. That year, the legislature approved an election consolidation measure, Assembly Bill 50, that pushed remaining municipal elections onto the statewide cycle. Like the Arizona and California measures, it passed by a wide margin in each house, perhaps because so many cities had already switched.

A TWISTING PATH

Already, ten US states require on-cycle local elections in almost all cases (though the exact count of states is somewhat hard to pin down, due to complexities of state laws). In about 20 US states, localities may already set their elections to align with national ones, and in these states, the trend is unmistakably toward consolidation.

Unfortunately, in the remaining states—about 20 of them— state law still bans election consolidation, including Alaska, Idaho, Montana, and Washington. In these states, reformers will need to convince legislators to let cities move their elections to when the voters show up: in November of even years. They can learn from the California-Arizona-Nevada model, in which a trickle of local election consolidation became a flood, and state action moved from allowing to encouraging to requiring consolidated elections. These precedents suggest that in non-consolidated states a first step might be to advocate for state policies that let cities choose when to hold their elections.

If legislators give cities the option, reformers will only need to get the question before voters. Then will come the easy part: voters will say “yes” by crushing margins. To them, election consolidation is, if nothing to get excited about, nonetheless a no-brainer. And why wouldn’t it be? It offers the benefits of boosting voter turnout dramatically, improving representation, enhancing the accountability of local governments, and saving taxpayer dollars.

Alan Durning

@SightlineThanks to Sightline’s senior research associate Jay Lee for analysis of the California Elections Data Archive, volunteer Todd Newman for research about laws in various states, and University of California, San Diego Professor Zoltan Hajnal for helpful review comments on an earlier draft of this article.