It Won’t Be RFK, But an Independent Could Win the White House in Future Years

35% of the National Popular Vote Could Easily be Enough

In the wake of CNN’s dismal presidential debate in June, it looked like independent and minor party candidates had a real opening to offer a better option than a would-be authoritarian with 34 felony convictions and an aging incumbent often unable to string together coherent answers. Joe Biden and Donald Trump were the least-liked major party presidential candidates in decades, and Robert F. Kenney Jr was surpassing 15 percent in some national polls.

But it’s now a new political world. The Democrats’ presidential nominee Kamala Harris is far more popular than Biden, while Donald Trump’s popularity also surged in the wake of surviving an assassination attempt. Only some ten percent of voters are unsatisfied with voting for one of them. RFK has dropped out of the swing states, and Cornel West, Libertarian Chase Oliver, and the Green Party’s Jill Stein might affect the outcome only by splitting the vote in the dreaded “spoiler” role.

Nevertheless, it’s not inevitable that a future challenge to the two-party system will fail. More voter choice is healthy for our politics, and better reflects the diversity of opinion and interests in modern America. Although our antiquated voting rules are far less equipped to handle greater voter choice than the ranked choice voting system used in Alaska and Maine, the combination of plurality voting and the Electoral College won’t necessarily deny success for challengers to two-party dominance. In fact, a strong independent could win an absolute majority of electoral votes with about 35 percent of the national popular vote.

Some analysts inaccurately suggest the Electoral College alone is an insurmountable barrier to independent candidates. In 2016, the noted analyst Norm Ornstein wrote that if an independent and the two major party nominees each won about a third of the vote, "no candidate would come close to the majority of 270 [electoral votes] required, under the Constitution, for victory." That would throw the choice of president to Congress and its absurdly antiquated rules - with the Senate picking the vice-president based on “one Senator, one vote” and the House picking the president based on “one vote per state delegation.”

While that would be possible if the independent only won a few states, it's not inevitable. To give an idea of what might happen when a presidential election features a strong third candidate, the FairVote team years ago simulated the results of a stronger performance by Texan Ross Perot when, in 1992 as an independent, he earned 19% of the vote against Democratic winner Bill Clinton (43%) and Republican incumbent George Bush (37.5%).

Perot's campaign was unusual. He gained ballot access in states, then abruptly suspended his campaign when his poll numbers declined, then restarted it in September. Despite his off-putting suspension, he ran reasonably well, including helping to deny a majority vote win in 49 out of 50 states. (A tough quiz question is what was the one state where Clinton won more than 50% – the surprising answer being his home state of Arkansas, now one of the nation’s most Republican states.) Still, Perot did not come close to winning any electoral votes and only finished second in Maine and Utah.

But everything would have changed if Perot’s vote share had approached his earlier poll numbers. Our simulation suggests that Perot would have won an Electoral College landslide of 343 electoral votes if he had earned 38% of the vote by doubling his vote share in each state and securing that increase equally at the expense of Clinton (down to 33.5%) and Bush (down to 28.0%) – a fair assumption based on analyses suggesting a nearly even split among Perot voters in their second choice.

In fact, Perot would have won an Electoral College majority of 313 electoral votes if his vote share had risen under these assumptions by just 16% to 35%, again coming equally from Clinton (down to 35%) and Bush (down to 29.5%). Notably under this scenario, Perot would have won his Electoral College majority even while losing the popular vote to Clinton. Our Perot 1992 simulator spreadsheet shows these different scenarios.

If the three-way vote had been close, there are scenarios supporting Ornstein's concern. For example, if Perot's vote share had risen only 15% to 34%, he would have won 241 electoral votes, sending the contest to Congress. There also would have been no Electoral College majority if Perot's vote had risen 16% to 35%, but he had drawn 60% of his vote from would-be Bush voters and only 40% from would-be Clinton voters.

But there's no reason that a future independent candidate couldn't rise to a larger share of the popular vote when voters are truly ready for a change. Independents have won several elections for governor when competing against two strong major party nominees, such as when:

Lincoln Chafee in 2010 won 36.1% In Rhode Island against 33.6% for the Republican and 23% for the Democrat.

Angus King in 1994 won 35.4% in Maine against 33.8% for the Democrat and 23.1% for the Republican.

Jesse Ventura in 1998 won 37% in Minnesota to 34.3% for the Republican and 28.1% for the Democrat.;

Walter Hickel won 38.9% in Alaska in 1990 against 30.9% for the Democrat and 26.2% for the Republican; and

Lowell Weicker won 40.4% in Connecticut in 1990 against 37.5% for the Republican and 20.7% for the Democrat

Furthermore, when one major party's nominee becomes seen as a "spoiler" and implodes, independents can run even better. Consider that in U.S Senate races, Angus King in 2012 in Maine won 52.9% over a Republican (30.7%) and Democrat (13.2%), while Joe Lieberman (running as an independent after losing the Democratic primary) in 2006 in Connecticut won 49.7% over a Democrat (39.7%) and Republican (9.6%). In addition Lisa Murkowski (running as a write-in after losing the Republican primary) in 2012 in Alaska also won with 39.5% over a Republican with 35.5% and a Democrat with 23.5%. Independent Bill Walker in 2014 was elected governor of Alaska with 48.1% against 45.6% for the Republican.

Independents can also rise sharply in the polls, especially when voters start seeing them as viable and consider them with less calculation. Polls in Jesse Ventura’s 1998 win in Minnesota are instructive. Ventura polled at 7 percent in June, rose to 13 percent in early September, and was up slightly to 15 percent in early October before surging to 23% later in October and ultimately winning with 37 percent. Independent Eliot Cutler nearly was elected governor of Maine in 2010, losing just barely with 36.5% to Republican Paul LePage with 38.3%. Yet only weeks before the election, Cutler was polling at only 11 percent, when he started his meteoric rise.

If Perot in 1992 had won similar popular vote victories as these independent candidates, he almost certainly would have earned a clear victory in the Electoral College. Even under our antiquated rules, an independent could win in a future presidential election if seen as viable and able to surpass 35 percent of the vote.

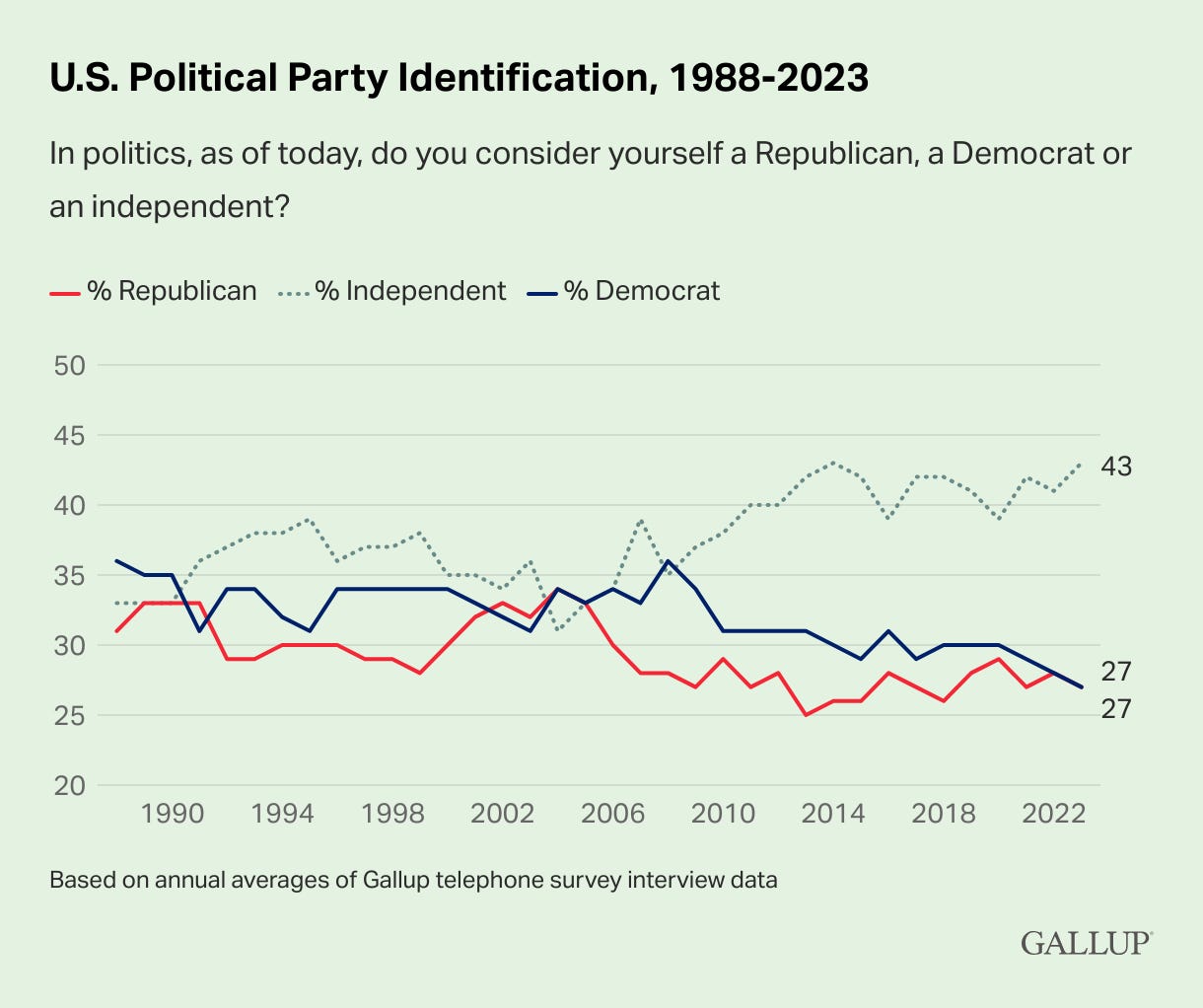

The trend lines for voters abandoning the major parties in their affiliation in the chart above suggests that it’s more than possible within the decade. A substantial and rising plurality of voters in the United States affiliate outside the major parties - and over in the United Kingdom, with the same plurality voting system, barely half of British voters this year cast a ballot for the two major parties. While our intense polarization between Republicans and Democrats serves to whip such independent-leaning voters into the two-party line, don’t count on it being inevitable.

To avoid Electoral College chaos scenarios coming with strong independent candidates, states have the power to join the National Popular Vote interstate compact, as already law in 17 states and DC. If states with collectively 71 electoral votes also passed the compact, it would be activated and in the next election guarantee that the national popular vote winner across all 50 states and DC will always become president. To accommodate more than two candidates, states also should adopt the proven alternative of ranked choice voting. Eventually, we can make such changes permanent via the constitutional amendment proposal that has been tried the most time in US history – direct election of the president, ideally twinned with the most efficient method of securing a majority via ranked choice voting.

This commentary draws from one I first published in Huffington Post in 2016.