Lee Drutman responds to Steven Hill: "Yes, Fusion does offer a new horizon for US Politics"

Drutman thinks fusion will best usher in "party-centered reform" that the two-party system so badly needs -- and maybe even proportional representation

[Welcome to DemocracySOS, a newsletter on the politics of political reform and the troubled US political system. If you’re already signed up, great! If you’d like to sign up and receive issues over email, you can do so here. This article from New America’s Lee Drutman is part of a three-part debate between Lee and DemocracySOS’s Steven Hill. Here is a link to Hill’s response to Drutman, and a link to Hill’s original article that Drutman was responding to.]

In a recent piece here on this DemocracySOS Substack (“Does Fusion Voting offer a new horizon for US politics?”), Steven Hill addresses the rising popularity of fusion voting. Though he notes some benefits of fusion, he is largely skeptical of its promise. As he concludes: “fusion voting does not fundamentally alter the troubling toxicities of America’s antiquated winner take all system.”

As a political scientist who studies electoral systems and the role of political parties in our democracy, I want to explain here why I see fusion voting as a powerful way to in fact address some of the “troubling toxicities” in the immediate term. I like it in the immediate term because it can create an instant home for anti-MAGA Republicans who want to support Democratic candidates (or punish Republicans) without supporting the Democratic party, managing the most immediate existential threat to democracy.

I like it for the long term because I also believe fusion voting creates a particularly promising pathway to fundamentally alter the destructive winner-take-all system. To move beyond the winner-take-all system means moving beyond the two-party system. Fusion is a pro-parties strategy that builds more parties. More parties can move us towards proportional representation.

The Need to Move Beyond Two Parties

Let me start out with a point of strong agreement. I concur with Hill: The winner-take-all, two-party/two-choice system is deeply problematic. In order to break out of the two-party doom loop, we ultimately need to move towards some form of proportional representation. Both of us have written extensively on this point.

Here’s where I think we disagree: Hill believes that the path to proportional representation more likely goes through ranked-choice voting. I believe that the path to proportional representation more likely goes through fusion.

I see fusion as more practical and tactical, and having many positive qualities in and of itself, particularly in countering the threat of an authoritarian far-right, even if it does not lead to proportional representation in the end.

By contrast, I see ranked-choice voting as less likely to lead us towards proportional representation, and of limited impact in addressing the authoritarian far-right turn in our politics.

This view follows from my strong belief in political parties as the essential institutions of modern representative democracy. Fusion is a party-centered reform. It encourages new parties to organize and form, because a ballot line is power.

Many countries have transitioned from majoritarian, winner-take-all systems to proportional representation systems. But all of those transitions had some multipartyism first. Multipartyism creates pressure for proportional representation, and facilitates the transition.

By contrast, ranked-choice voting is a candidate-centered reform. Ranked-choice voting has many positive qualities that work well in primary elections and local nonpartisan elections, where small electorates are trying to find compromise candidates amidst generally broad agreement. But at a larger scale, parties shape and organize politics. Candidates come and go. Ranked-choice voting focuses on candidates. Fusion focuses on parties.

To fuse or not to fuse

In arguing against fusion, Hill compares the strategies of the Green Party to the Working Families Party (WFP) in New York, one of only two states where fusion remains legal and part of the political culture.

The WFP is a fusion party. It often supports progressive challengers in Democratic Party primaries. It typically aligns with the Democratic Party for the general election, not just because state law makes the party pragmatically support the top of the Democratic ticket in order to maintain its ballot line, but also because the WFP doesn't want to split the liberal-left vote and help elect Republicans.

The WFP almost never runs “stand-alone” candidates. Instead, its mantra to voters is: “Vote for the candidate you prefer under the party label closest to your values.. In 2020, Biden received 4.8 million votes in New York under the Democratic Party label, and almost 400,000 more under the WFP label. That’s a lot of votes, and over the last 25 years the year-in, year-out work of interviewing candidates, running issue campaigns, training volunteers and turning out its supporters has made the WFP a serious actor in state politics. Politicians court the party’s support, and the WFP is famous in the state for extracting serious policy concessions in Albany in return for its support.

Fundamentally, because the Working Families Party delivers a modest but real share of the vote to winning candidates, it has some proportional influence on how those leaders govern. Not control, but influence. This is obviously not full proportional representation. But within the system of single-winner elections, it is as close as one gets.

The WFP has played a central role in winning minimum wage hikes, paid family leave, public financing of elections, an end to the Rockefeller Drug Laws, higher income taxes on the wealthy, rent regulation, and the nation’s best state-level climate legislation. Did they get everything they wanted? Not even close. Did they improve the conditions of life for the non-wealthy? It seems clear they did.

The Green Party, by contrast, opposes fusion voting and exclusively runs its own candidates year after year. Its leaders know, and more importantly the voters know, that stand-alone candidates have no chance of winning an election and wielding governmental power.

Green Party members do not participate in the rough-and-tumble of policy making in Hartford or Albany. They do not produce a meaningful proportion of any winning candidate’s total. The Green Party is a protest party. Elected officials can safely ignore them.

Ranked-choice voting might allow stand-alone candidates of the Greens or other such parties to win a few more votes by eliminating the spoiler effect. But it won’t improve their likelihood of winning, so it can’t solve the problem of candidate entry. Evidence suggests that while implementation of ranked-choice voting boosts candidate entry initially, that effect quickly dissipates. Once marginal challengers realize they still have no shot of winning, they stop bothering. This is why RCV is unlikely to lead to proportional representation.

Whither the Center?

In addition to its qualities of party-building, I find fusion voting compelling because it offers a unique opportunity to rebuild a vanishing political center. Hill notes this argument but finds it wanting. As he writes:

"some fusion advocates feel that it can empower moderate political parties to act as a bridge between the polarized major parties, and win support from independent voters. But there is no real historical precedent for this, and it seems unlikely because any candidate or party that is trying to appeal to voters from both political parties is likely to appeal to none of them. The mushy middle seldom achieves electoral success in US politics.”

The question of “historical precedent” is a relevant and important one.

First, let’s acknowledge that in recent history, fusion parties have primarily existed on the edges of the political spectrum, not the center. This is because fusion parties emerge where representation is scarce. Historically, the New York Democratic Party and the New York Republican Party have been dominated by moderates. Thus, representation was lacking in the more progressive and conservative parts of the political spectrum. Fusion parties responded to this lack of representation. They didn’t have the support to win outright. But they could represent the share of the electorate that didn’t feel represented, and give them a voice and an identity and a way to participate.

Over the last decade, the political landscape has changed dramatically. The political center has largely collapsed as the parties have pulled apart. The current political moment represents something truly unprecedented in modern US history — deep and substantive polarization in the American party system. The political center is the most under-represented part of the electorate. The “mushy middle” — once dominant in US politics — is now just mush.

Still, whatever one’s political ideology, democracy does not function well (or at all) when politics becomes deeply divided and the center collapses. As Hill notes, the dangers of winner-take-all elections are real. And they are most dangerous when the differences between the two sides are stark. It is hard to have a democracy without a genuine political middle. The middle provides flexibility and balance, a counter to partisan extremes.

Today, after a decade of doom-loop partisan politics, the political middle in US politics is not large. But even if it is roughly 10 percent of the electorate, that 10 percent holds the balance of power. Unfortunately, they have no way to harness that power under the current system. A moderate fusion party, such as the Moderate Party of New Jersey, could ensure that those voters have a home, an identity, and the ability to build a healthy middle in politics.

This, then, is the immediate value of fusion voting. In the short term it will create a space for a pro-democracy political party of the center, made up primarily of anti-MAGA Republicans, to emerge. This is a good thing. American democracy likely rests on the organization and coherence of this group of voters. A fusion party can organize this group into a coherent voting bloc. A non-fusion party is just a spoiler, or under RCV, a non-spoiler in constant need of candidates.

Candidates come and go. But political parties exist from election to election. They organize voters and develop identities and policy programs. Parties are essential institutions of representation. Weakening parties through candidate-oriented reforms does not result in stronger democracy.

When parts of the electorate are unrepresented, they can form a party, and express their influence by providing a share of voters to a major party candidate. Fusion thus responds to un- and under-represented voters. The portions of the electorate that are un- or under-represented shifts over time.

The historical precedent of fusion, which was widely used in dozens of states in the 19th century, is that it creates this opportunity. Readers should familiarize themselves with the role that fusion parties played during Abolition and then during the great farmer-worker upsurge of the post Civil War era. We once had a thriving multi-party democracy in America, and we desperately need one again.

The (con) fusion canard

Hill distinguishes between full, or disaggregated fusion, and partial or aggregated fusion. The terms are confusing and lead to some common mistakes.

In a system where fusion is legal, major and minor political parties join together in temporary alliances to nominate the same candidate: two parties “fusing” in support of the same candidate, but for different reasons and under distinct banners.

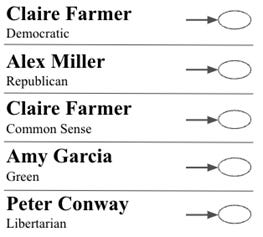

FIGURE 1: “DISAGGREGATED” FUSION BALLOT ILLUSTRATION:

This traditional form of fusion involves tallying candidates’ totals on each ballot line separately and then adding them together to determine the winner. Hence the term “disaggregated fusion” because the vote totals by party are initially separate.

FIGURE 2:

A related but qualitatively different system – sometimes confusingly referred to as “aggregated fusion” or disparagingly as “fat-free fusion” – persists in Vermont and Oregon. In these states, it is possible for two parties to nominate the same person, but both party labels are printed on the general election ballot next to the candidate’s name – so there is only one square (or circle) on the ballot for that candidate. The minor party is not afforded the opportunity to create a distinct identity and demonstrate its strength (or reveal its weakness) with the voters. Note the difference between this and Figure 1, where the candidate’s name appears more than once on the ballot.

FIGURE 3: “AGGREGATED” BALLOT ILLUSTRATION

Full fusion is the real deal: each party gets its own ballot line, the votes are tallied separately by party and then added together to produce the final outcome. In full fusion, the minor party gets its votes counted and can demonstrate its strength

It goes without saying that the people who favor a multi-party democracy should prefer the traditional “full” fusion system over the dual labeling system. Only in the former does the minor party get a chance to build over time, translating their vote totals into meaningful power. The system itself encourages stronger parties to form.

A second common mistake about fusion sometimes gets made goes this way: Fusion sounds good, but it will clutter the ballot with too many minor parties who will confuse and scam the voters. This was Andrew Cuomo’s position during his attempt to destroy New York State’s minor parties.

But there is zero historical precedent for this. Fusion voting has rarely generated more than five parties. That’s what was generally the case when fusion was practiced all across the land in the 19th century, and it’s true in both Connecticut and New York today. Voters can keep four or five parties straight. They’re not dumb. Most countries around the world have at least this many parties, if not more.

The Future of Fusion

Can fusion, once widely legal in the United States, return? To me, the fact that it was once widely used throughout the country is a powerful argument. It is part of the American tradition.

Another powerful argument for pursuing fusion is that many state constitutions have strong provisions around freedom of association, and state laws that prevent two parties from fusing in support of the same candidate clearly violate these fundamental rights. State by state, a careful legislative, ballot measure or legal strategy could have a big impact. This makes fusion do-able, and at scale.

As more parties form under fusion, they may ultimately want their own representatives in the legislature, rather than simply endorsing major party candidates. This would make them supporters of proportional representation. And because they will now have the leverage a ballot line affords, they can use that ballot line to push for full proportional representation. Major parties might also prefer to have full proportional representation as well, to be able to run more clearly on their own.

To be sure, political reform is a very difficult task. Most reform campaigns fail. Yet, some succeed. We are in a political moment of great uncertainty. It is moments like this when major reforms become most likely. If we are entering a fourth great era of democracy reform in America, and I believe we are, we should be thoughtful and rigorous about the path forward.

The Bottom Line - The Value of Multiple Parties

I agree wholeheartedly with Hill that “America’s antiquated winner take all system” is breeding “troubling toxicities.” And I agree that proportional representation is the best solution.

But the core question among reformers appears to be whether the pathway to proportional representation goes through parties or candidates.

Looking at history, it’s clear to me that the pathway can only go through parties. Thus, if we want proportional representation, or even better representation within the existing single-winner system (and remember, some offices are inherently single-winner), we need more and better political parties. This is why I like fusion, and why I also prefer an open-list system of proportional representation to a candidate-based system of ranking, the single-transferable vote.

The value of fusion is that it creates more parties, who can demand more and better representation by virtue of organizing a consistent share of the electorate across multiple elections and building a sense of identity and collective power. (note: I’ve been working on a long paper on the importance of party-centered reform, which will be published soon.)

By contrast, ranked-choice voting, and especially the combination of ranked-choice voting with a two-round primary, are candidate-centered reforms. They do not encourage political parties to form and organize. They encourage candidates to compete as independents, or as different flavors of Democrats or Republicans, preserving the pathological two-party system. Ranked-choice voting certainly has some positive qualities (it would be profoundly useful in party primaries). But it is not a pathway to more parties or proportional representation.

Lee Drutman @LeeDrutman

I learn something new every time I read this blog. I hadn’t thought of RCV as candidate-centered reform, but now comparing it to fusion voting, I see the contrast to party-centered reform. I’ve been thinking of RCV as voter-centered reform.

It seems that over time our political parties have become entrenched in their right to wield power instead of their privilege to serve they way voters want them to. Won’t more strong parties result in the same scenario and individual voters still be in the same spot we are now.

What about the fairly large percentage of Americans who aren’t “joiners” by nature? I’ve been thinking of RCV as a way for them to fully be heard without forcing them to choose between parties first, then specific candidates? Sort of like parties being the middlemen. (Although pondering my support of union organizing, I do see the value of organizing parties. I’m just not sure that government has to be run by faithful party joiners who become more attached to their party than their voters).

And I hadn’t been aware of the widespread adoption of fusion in the 19th century. I’m curious to know why it all but disappeared.

I was surprised by Mr. Drutman's argument here. I read his book, "Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop," which was very pro-RCV. And that was written in 2019 -- hardly a lifetime ago!

Mr. Drutman -- if you're reading this, could you elaborate on what changed in your thinking? Was there some political event that changed your mind?