Lessons learned: the four factors that result in election success for women

New report on women's representation in 100 largest cities highlights importance of RCV, public campaign financing, term limits and support groups for women candidates

Since the November midterm elections, we’ve already been reminded on at least two separate occasions of the ways ranked choice voting could solve issues born out of political polarization. From the costliest election of 2022 – the Georgia runoff election – to the time-consuming election for Speaker of the House of Representatives (requiring the most rounds of voting since 1859), the need for reforms like ranked choice voting is glaringly obvious.

But as Vice President Kamala Harris so aptly said, "The status of women is the status of democracy." So, how did women do in 2022?

Midterms 2022: Bittersweet Outcomes for Women

First, the good news. The record for most women serving in Congress was once again broken, increasing from 147 (the record set during the previous 117th Congress) to 149. One seat was gained for women in the House of Representatives and the other in the Senate.

Black and Latinx women’s representation also increased in the House. In fact, there are now a record 27 Black women and 18 Latinx women. With losses for black female senatorial candidates Val Demings in Florida, Cheri Beasley in North Carolina and Krystle Matthews in South Carolina, there are still no Black women in the Senate. Catherine Cortez Masto barely held her Senate seat in Nevada by 0.5% of the vote, so we will continue to have one Latinx woman there. She also happens to be the only Latinx woman senator in our nation’s history elected to that bastion of white male privilege, which today is 76% male and 88% white.

We also saw some pretty significant progress for women’s representation in gubernatorial positions. There were 25 women who ran for governor this year and of those, 12 won. This puts us almost halfway to gender balance for governors — much closer to parity than ever, but with still a long way to go.

The last few elections sported headlines raving about another “Year of the Woman.” This phrase was first used to describe the 1992 U.S. Senate election where the number of women senators grew from a paltry two to a slightly less than paltry six. This phrase resurged again in 2018 when women won in record numbers, and has continued to be used in every election since.

But here’s why the results are so bittersweet. Don’t get me wrong, breaking records for the number of elected women is important, and shows real progress. However, even though the overall number of women in politics has increased, if we continue at this current rate, we won’t reach gender balance in governance for another 118 years! That is -- not in any of our lifetimes.

Plus, calling it Year of the Woman is problematic for a myriad of reasons. The sentiment is summed up perfectly by the inspiring former Director of the Center for American Women in Politics Ruth Mandel and Professor Irwin Gertzog in 1992 when “The Year of the Woman” was coined:

“Naming a special year for women in politics seems quintessentially American — an encapsulation and packaging of a great process of social and political change into one year’s product. This year’s new product line is political woman. If she does not sell, or sells only in very limited quantities, we may not invest much in marketing her again. The political woman as fad, good for one year’s sales, then discounted or discarded.”

Having marginally broken a few records is not indicative of true progress. When we dub marginal progress as a "Year of the Woman," we lose focus on the reality of the ever present barriers women face throughout the entirety of the political and electoral process. These women may have won their elections, but representation in Congress remains at less than 28% and systemic barriers such as inequitable campaign funding or our winner-take-all elections work to keep that percentage low.

So, what’s next?

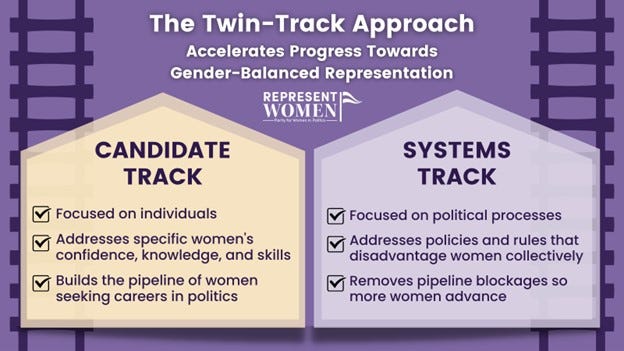

If this election has taught us anything about what is needed to achieve gender balance in our governments, it is this: we cannot rely solely on encouraging more women to run. We need systemics reforms in addition to individual candidate support in order to effectively increase women’s representation.

This exact approach, called the twin-track approach, is what RepresentWomen identified as the central answer to Why Women Won in 2021 on the New York City Council. RepresentWomen released The Twin-Track Ecosystem in the 100 Largest Cities in October 2022 where we expanded upon and re-evaluated our NYC findings by researching: 1) women’s representation in the 100 largest cities in the U.S., and 2) which of the key ingredients to gender balance observed in NY City are also present in these cities. The report concludes with a list of guiding takeaways, aimed at changemakers interested in bringing the best practices and strategies that worked in New York City to other major cities.

The twin track approach consists first of the candidate track, in which women candidate groups (WCGs) like The New Majority NYC provide specific support to women candidates by recruiting, training, and generally navigating them through the election process.

The second component is the systems track which manifests as three reforms: ranked choice voting, term limits, and public financing/matching campaign funds programs that remove the barriers entrenched into our political systems.

On their own, both of these strategies can help to increase women’s representation. But, when these two tracks are used in tandem, there is even greater potential to open more and more doors for women. New York City was a prime example of this opportunity, with women’s representation jumping from holding 28% to 62% of seats on the city council (31 out of 51 seats).

Thus in its report, RepresentWomen names these four factors as the core of the twin-track approach for electing women: candidate groups (WCGs) and the above three electoral reforms. RepresentWomen also identifies several promising cities where some of the conditions that propelled women’s representation in New York are already present. The cities of San Francisco, Oakland, Denver, Long Beach, and Los Angeles are “good candidates for additional research, advocacy, and investment.” We provide a few recommendations based on the specific environment of each city.

To improve the level of women’s representation in cities where it has not been achieved:

From the report: “Moving forward, our first option is to focus on the cities that already have at least half of the twin-track factors present, but do not have parity at the local level: Los Angeles and San Francisco. In Los Angeles, there is an opportunity for ranked choice voting and a local women’s candidate group to be introduced. Though San Francisco technically already has all four twin-track factors, there is room for building on the infrastructure that is already there (RCV, term limits and public campaign financing) to ensure that more women are running and have the resources they need in each election, particularly in years following council turnover due to term limits.”

To sustain gender balance in cities where it has currently been achieved:

“Denver and Long Beach would benefit from having ranked choice voting and local WCGs. Since both have small councils and term limits, women’s representation is likely to fluctuate in the future without additional support.”

Again and again, our democracy has failed to deliver on its promise of creating a voter-first, voter-driven system by keeping outdated voting systems, such as the winner-take-all rule, in place. As a result, our country’s political leaders do not adequately represent “We ALL the People,” and create policies and practices that do not meet the true needs of all Americans.

But we imagine a democracy where elected officials and appointed leaders are held accountable for creating legislative policies that ensure more women can run, win, serve and lead in political positions.

Alissa Bombardier Shaw @alissashaw_