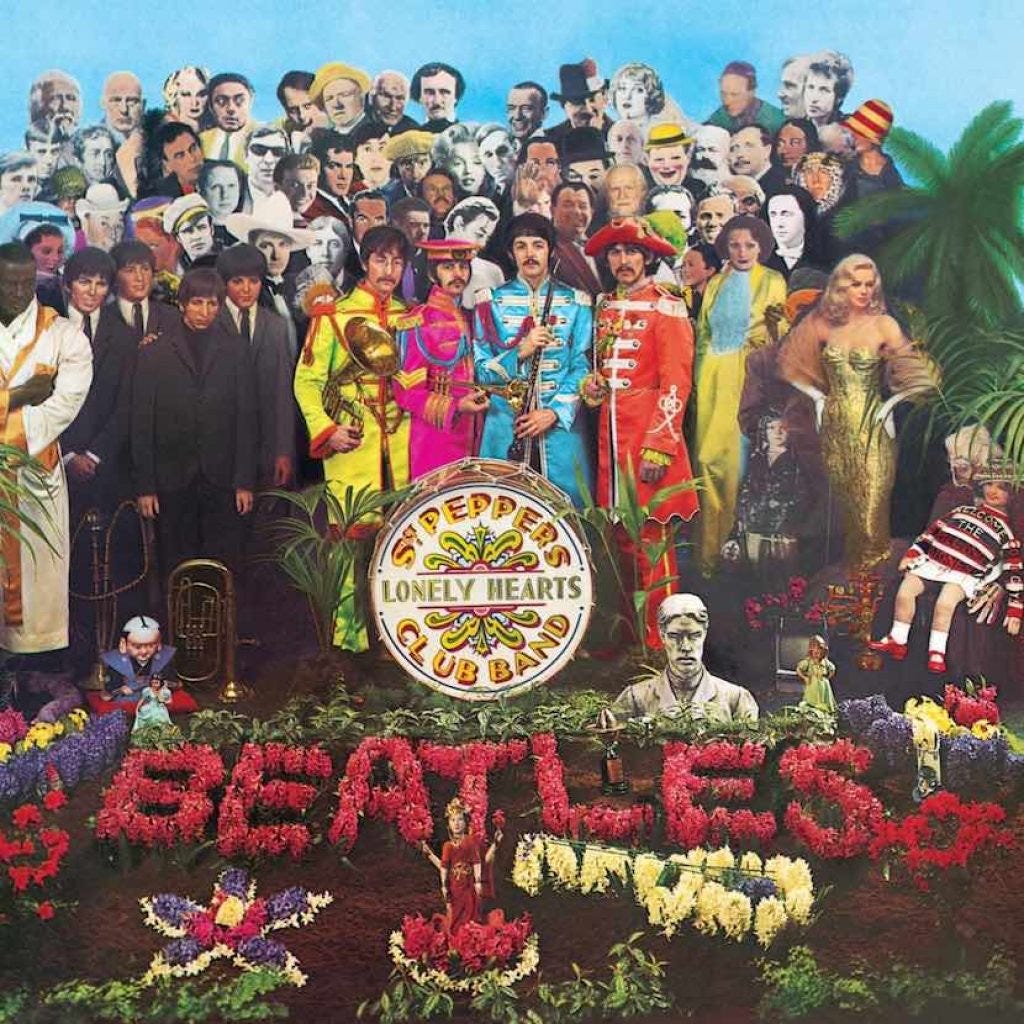

ReformHistory: “It was twenty years ago today– Sgt Pepper taught the band to play”

Ranked choice voting made history in San Francisco, March 2002

March 5, 2002. That was the historic day when the national movement for ranked choice voting took its first giant step forward. Twenty years ago in March. On that night, following a grueling, months-long campaign, we passed a voter initiative in San Francisco for ranked choice voting (RCV). Against all the odds, against all the money from entrenched interests that was stacked against us, FairVote (which then was known as the Center for Voting and Democracy), fought a hard campaign to pass our reform, known as Proposition A. It was the first victory for electoral system reform in the United States since the 1950s.

I still remember that moment like it was yesterday. As the campaign manager, I had led a merry band of idealistic election reformers who dared to believe we could convince an entire city of 800,000 people that a new way of voting was the wave of the future. “The way democracy will be,” as my colleague (and longtime CVD/FairVote director) Rob Richie was fond of saying.

Our opponents, mostly the usual mix of political consultants and downtown business interests opposed to change, had spent gobs of money to kill Proposition A. They outspent us about 10-1, with negative TV and radio ads and they mailed tens of thousands of citywide mailers, attempting to slander our efforts. One mailer showed a photo of a National Organization for Women march and said, “If Proposition A passes, women’s representation will suffer.” Just one problem – the local chapter of NOW actually had endorsed our measure, as had national woman’s leaders like Patricia Ireland and Ellie Smeal.

Another mudslinging mailer showed the famous photo of a lone Chinese man standing in front of the line of tanks at Tiananmen Square in June 1989, after the Chinese government's deadly crackdown on protesters. The message said, “If Proposition A passes, your right to vote will be taken away,” and it was mailed to Chinese surname households all across the city. That was downright insulting. Not only had most prominent Chinese and Asian political organizations and leaders endorsed our measure, but one of our chief goals in waging this battle was to empower traditionally underrepresented communities (which RCV elections in subsequent years would succeed beautifully in doing).

Our opponents had no shame. They were willing to do and say anything to stop reform. As the polls closed on Election Night, I was exhausted. I had been awake for nearly 36 hours at that point, directing the troops (over 100 volunteers), transporting signs and door hangers, leading a wee hour lit drop to our most supportive precincts, giving media interviews, and urging on my teams of precinct walkers, street sign holders, phone bankers and more. One photo from that time, which I recently pulled out of a shoebox, showed me talking into two telephone receivers at once, one for each ear. I look like a strange kind of insect, with the portable phone antennas extending past the top of my head. I remember scanning my to-do list, looking for the next task, unable to stop my campaign fever, flying along on adrenaline and a refusal to lose.

Finally, my co–campaign manager and fellow conspirator from the Center for Voting and Democracy, Caleb Kleppner, looked at me and said, “Hey, what are you doing? The polls have closed. Election’s over.” I realized he was right. There was nothing left to do, except wait for the results. I slid into a chair at our campaign headquarters, exhausted, and with a sinking feeling. Our prospects for success suddenly looked grim.

The reform we were trying to pass, ranked choice voting (or instant runoff voting as we called it at the time – in a future post, I will tell the odd story of how the name got changed for crazy random reasons). As an advanced electoral method, RCV allows voters to sincerely express the full range of their electoral preferences by ranking multiple candidates according to their first, second, third and more choices. If your first choice doesn’t win, your vote goes to your second selection—that’s your runoff choice, the candidate you prefer if your favorite candidate can’t win. The goal is to elect candidates who have support from more than 50 percent of voters and to determine that in a single election. Voters are liberated to vote for the candidates they really like instead of choosing the “lesser of two evils,” or worrying about voting for a “spoiler” candidate who might split a constituency vote and result in non-majority winners.

In effect, RCV asks voters to tell us more about themselves. OK, you know who your favorite candidate is, but tell us more—tell us your second favorite in case your first choice doesn’t have enough support to win. OK, you’re a moderate Democrat, but what about this moderate Republican candidate? Might that candidate be acceptable as your second or third choice? Or maybe you are a Libertarian Party or Green Party supporter—tell us who your second- or third-choice candidates might be in case your top candidate can’t win. Voters can think more about which candidates they like regardless of partisan labels. And this in turn fires the synapses of voters in ways that the current “highest vote-getter wins all” system can never do.

US elections are filled with examples of third party candidates in races for president, U.S. Senate and House who very likely spoiled the results for one of the two major party candidates. In the 2020 presidential election, Libertarian candidate Jo Jorgensen’s share of the vote was much higher than the margins between Joe Biden and Donald Trump in the key battleground states of Georgia, Wisconsin and Arizona. If Trump had won those three states, he and Biden would have tied in the Electoral College vote at 269 apiece, and all hell would have broken loose.

Or flash back to the presidential election in 2000 – with RCV, the 97,000 Ralph Nader voters in Florida would have had the option of ranking a second choice. No question, tens of thousands of them would have ranked Al Gore, who would have received all those “instant runoff” votes, winning Florida instead of losing it to George W. Bush by 537 votes. For that matter, in New Hampshire, Nader’s 22,000 votes was three times the vote difference between Bush and Gore. If Gore had won either of those states, he would have become president. History would have been different.

So using an advanced electoral system like ranked choice voting in a single winner race produces fair, more majoritarian results, and can change outcomes. And RCV leads to a more satisfactory experience in the voting booth because voters are no longer trapped in the dilemma of always picking the “lesser of two evils.” You can cast your vote for your favorite candidate, knowing that if your favorite can’t win, you can give your vote to your second choice.

Waiting for the initial results that Election Night twenty years ago, I reflected on the fact that no ranked ballot system like RCV had been enacted in the United States in many decades. Americans are used to thinking that we are the paragon of democracy, that the way we elect our representatives is the best — indeed, the only — way. Most Americans, even many political scientists, are unaware of the vast array of electoral methods available and used in other nations, almost all of them better than those we currently use. With that kind of hubris, it’s no wonder we had a dangerous insurrection following the 2020 presidential election, and an electoral meltdown following the presidential election in 2000, and nearly again in 2004.

Despite these recurring electoral dysfunctions, many Americans remain very closed-minded about trying other methods. Yet, against all those odds and more, we in San Francisco had been audacious enough to believe that we could convince an entire city to take a chance on a new method like RCV.

That night, twenty years ago, victory was ours. We had managed to pass one of the most significant electoral reforms in decades. San Francisco went on to hold its first RCV election in November 2004, and the city has now used it in 15 different election years for dozens of races at the local level to elect the mayor, Board of Supervisors (city council), district attorney and more. The Proposition A victory was momentous because it showed that significant political reform was possible.

But the movement for RCV was just getting started. Since then, other cities and states have passed ballot measures for ranked choice voting, including New York City, Oakland, Portland (Maine), Santa Fe, Minneapolis, St. Paul, numerous cities in Utah and other cities, a total of over 50 cities. The states of Maine and Alaska now use RCV for some of their federal races, and the Republican Party in Virginia used it in its gubernatorial primary in 2021, as did Democratic primaries and caucuses in Wyoming, Nevada, Hawaii, Kansas, Maine and Alaska. Legislative bills for ranked choice voting have been introduced into state legislatures in dozens of states, and the FairVote-sponsored Fair Representation Act seeks to use RCV to elect the House of Representatives in multi-seat districts, a form of proportional representation. Support has been gained from the left and the right.

Ranked choice voting, both for single-winner elections for executive offices, as well as multi-seat elections for our local, state and federal legislatures, is the right kind of reform for our country at this time. In a recent Gallup poll, 62% of Americans say that a viable third party is needed, with a record 63% of Republicans expressing third party support. Yet our eighteenth-century electoral methods, whether for Congress, the president, or state legislatures, create and reinforce the two-party system. More modern methods such as RCV are far better suited for our twenty-first-century politics and our multi-everything society.

Indeed, at this point in the evolution of the nation’s political landscape, the case for RCV is the case for democracy itself. All Americans deserve representation, no matter where they live or what they believe. But our current "single-winner plurality" system, with its zero-sum, winner-take-all dynamics, will never be able to deliver that.

It’s time to think like the Founders of our nation once did – outside the old box, with invention and inspiration, guided by a zeal for renewal instead of clinging to the flypaper of old ideas.

Steven Hill @StevenHill1776

"In the 2020 presidential election, Libertarian candidate Jo Jorgensen’s share of the vote was much higher than the margins between Joe Biden and Donald Trump in the key battleground states of Georgia, Wisconsin and Arizona. If Trump had won those three states, he and Biden would have tied in the Electoral College vote at 269 apiece, and all hell would have broken loose."

If all states had implemented Top-Two Electoral College Vote Proportional Allocation (T-2PA/J), Biden would have won with 276 votes compared to Trump's 262 votes.

"Or flash back to the presidential election in 2000 – with RCV, the 97,000 Ralph Nader voters in Florida would have had the option of ranking a second choice."

If all states had implemented T-2PA/J, Gore would have won with 270 votes compared to Bush's 268 votes.

For an explanation of T-2PA/J: http://fairelectionadvocates.org/index.php/campaigns/campaign-menu