The Magnet and the Merry-Go-Round

By Greg Dennis: Why Ranked Choice Voting is superior to Condorcet Voting as a tool for political depolarization

[Editor’s note: DemocracySOS welcomes guest author Greg Dennis from Voter Choice Massachusetts. The Bay State has been a hotbed of Ranked Choice Voting (RCV) activism, substantially due to the efforts of Greg and others. Currently 27 communities in Massachusetts are actively pursuing RCV, including Boston. Proponents have won the support of Gov. Maura Healey, both US Senators Elizabeth Warren and Edward Markey, six of Massachusetts’ nine US House members, several former governors, both Republican and Democrat, a number of good government groups, labor unions, NGOs and state and local elected officials. The list of endorsers is impressive.]

[A good-natured warning about Greg’s article — this one is going to get a bit wonky. He engages in some rigorous comparative analysis examining RCV vs Condorcet Voting, looking at the pros and cons of each. If you give the article a try, I think you will find it illuminating and rewarding.]

Ranked Choice Voting (RCV) is one of the fastest-growing voting reforms in the United States. Twenty-three years ago, the only US jurisdiction using RCV was Cambridge, Massachusetts, home to fewer than 60,000 registered voters. Today, RCV is used for public elections in 50 American jurisdictions, including 2 states, 3 counties, and 45 cities, reaching nearly 14 million voters. While new statewide adoptions fell short this past November, Ranked Choice Voting made net gains with wins in Washington, DC and Oak Park, IL, and the state of Alaska and the city of Bloomfield, MN voted to continue using RCV for their elections, too. Despite the speed bumps, for more than two decades we’ve seen a long, steady march toward greater RCV adoption nationwide.

As Ranked Choice Voting has grown in popularity, its benefits have become progressively more apparent. Numerous studies have found the adoptions of Ranked Choice Voting to have boosted turnout, promoted campaign civility, and diversified representation. Moreover, the foremost criticism of RCV – that it is too “complicated” for voters – is being steadily dispelled by the mounting real life experience of voters actually using it. As survey after survey demonstrates, once voters cast a RCV ballot, they tend to like it, understand it, and want to keep it.

Naturally, any reform will draw its share of detractors, and RCV is no exception. While most critics of RCV prefer to keep our existing plurality system, not all are defenders of the status quo. A small number of detractors do agree with us about the failures of plurality voting; however, they would prefer those problems be addressed with a different alternative voting method instead. While there are myriad alternative voting systems, and an enthusiastic advocate for just about every one, this essay focuses on the recent arguments made by proponents of “Condorcet methods,” a class of voting systems named after the brilliant 18th century French philosopher and mathematician Marquis de Condorcet, and explained in greater detail below.

This essay focuses on Condorcet advocates not because they are particularly numerous, but because their arguments, while ultimately flawed, are grounded in a kernel of truth. In short, these critics argue that Condorcet would be more effective than RCV at reducing political extremism due to its ability to elect a compromise candidate in a polarized political environment. While this theory has some mathematical appeal, it overlooks the ample real-world experience from actual RCV elections and fails to account for the differing strategic incentives offered by both systems. An alternative theory, one better supported by the available data, shows why RCV is superior to Condorcet as a tool for depolarization, and for fixing the broken plurality system used in the US today.

The Case for Condorcet Voting

To understand the rationale for Condorcet voting methods, let’s start from a purported flaw in RCV that Condorcet proponents like to highlight. Namely, they point out that RCV may fail to elect a compromise candidate when the electorate is polarized. The canonical example involves three candidates – one on the left, one on the right, and one in the center – where candidate Center trails candidates Left and Right in first-choice support. Here are the ranked ballots for one such scenario involving 100 voters:

No. of voters First choice Second Choice Third Choice

44 Right Center Left

43 Left Center Right

8 Center Left Right

5 Center Right LeftAssuming these rankings reflect the sincere preferences of the voters, the Center candidate is preferred by a majority of voters in head-to-head match-ups against either Left or Right individually. Specifically, in a head-to-head matchup of Center vs Right, Center would win with 56 votes (43+8+5) to 44 votes; and in a Center vs Left match-up, Center would win 57 (44+8+5) to 43. A candidate like Center that beats every other candidate in head-to-head theoretical matchups is called the Condorcet winner. Although a Condorcet winner isn’t guaranteed to exist in every election (due to a phenomenon known as a Condorcet cycle), a voting system that guarantees the Condorcet winner is elected whenever one does exist is known as a Condorcet-compliant method, or a “Condorcet method” for short.

A few more technical definitions will come in handy. While the Center candidate above is the Condorcet winner, the Right candidate is a Condorcet loser, meaning they lose every head-to-head matchup. Finally, the voters who ranked Left > Center > Right and those that ranked Center > Left > Right together form a majority coalition, because they support a common set of candidates (Center and Left) over all others (Right) and combined constitute a majority of all voters, 51 (43+8) of 100 voters.

In the above scenario, any Condorcet method by definition elects Center, because again, Center is the Condorcet winner. But both plurality voting and RCV choose someone else. Under plurality, candidate Right is elected, because Right has the most first choices and plurality ignores later preferences entirely. RCV and Condorcet proponents generally agree that this is the worst possible outcome, as Right is a Condorcet loser and is the only candidate not supported by the majority coalition.

Ranked Choice Voting, on the other hand, elects Left, a candidate who is both supported by the majority coalition and not the Condorcet loser. In fact, RCV is guaranteed to always elect a candidate from the majority coalition and never elect the Condorcet loser. However, as demonstrated in the example, RCV is not guaranteed to elect the Condorcet winner. This scenario has been colloquially referred to as the “center squeeze,” referring to the Center candidate’s support ostensibly being siphoned off by the Left and Right candidate, causing Center, the Condorcet winner, to be eliminated in the first round of a RCV tally.

For some academics, the center-squeeze possibility – this potential failure to elect a Condorcet winner – is not a negligible curiosity that can be quietly tolerated. For them, it is a fundamental threat to RCV’s capacity to substantially moderate our politics. Professors Nathan Atkinson and Scott Ganz have warned about an “extremist bias inherent to … ranked choice voting.” Professor Ned Foley is concerned that RCV may elect the “most polarizing candidate.” To see why they’re wrong, let’s first look at the data.

A Plea for Real-World Empiricism

With the level of concern expressed by Condorcet proponents about the center squeeze scenario, one might assume that RCV fails to elect the Condorcet winner with significant frequency. If that is the case, one would be mistaken. Indeed, when Professor Nicholas Stephanopoulos of Harvard Law School studied the question, he found the opposite to be true.

In his 2024 paper “Finding Condorcet,” Stephanopoulos calculated that Condorcet winners were elected in 181 of 183 races in the US over the last two decades and in 191 of 193 races in Australia and Scotland. As he concluded, RCV “functions essentially as if it were a Condorcet-consistent method, electing the Condorcet winner almost all the time,” and as such, “there are only minor majoritarian gains to be had by switching … to a Condorcet-consistent method.”

The full data set of RCV elections in the US makes an even stronger case. Out of more than 800 single-winner RCV elections in US history, RCV has failed to elect the Condorcet winner exactly twice, or less than one quarter of one percent (0.25%) of the time. Even if we restrict ourselves to only RCV elections featuring 3 or more candidates, it’s still only 0.4% of the time. That’s a factor of 100 lower than the statistical simulations of Atkinson, Foley, and Ganz, a fact that speaks to the importance of real-life empiricism, and as a corollary, the unreliability of mathematical models.

Condorcet fans should be thrilled to see a fast-growing voting reform demonstrating a near-perfect level of Condorcet efficiency. Even if one believes that center-squeeze scenarios weaken RCV’s propensity for moderating our politics, it’s implausible that they could be consequential at such a low frequency. Those who insist otherwise owe us either a careful argument as to why such rare events could have a substantial impact, or an argument as to why they might be more common in the future. We haven’t seen any of either. Instead, the only genuine, real-world evidence they’ve marshalled are anecdotes. And, again, there’s only two of those to choose from, out of many hundreds of races.

The anecdote that’s featured most prominently in the recent pro-Condorcet commentary is the August 2022 special election for Alaska’s US House seat, to fill the seat left vacant after the death of Republican incumbent Don Young. Democrat Mary Peltola beat Republican Sarah Palin in the final round of that RCV election, but the rankings indicated that moderate Republican Nick Begich would have beaten both Peltola and Palin in head-to-head contests. In the phraseology of the center squeeze scenario, Begich is that Center candidate who was “squeezed” between the Left candidate Peltola and the Right candidate Palin.

Did this election demonstrate the propensity for RCV to elect an “extremist?” Far from it. Peltola was a clear moderate who endorsed moderate Republican incumbent Lisa Murkowski for Senate. Moreover, she went on to win reelection to a full term a mere three months later – that time as the Condorcet winner, no less – and then clocked in as the most popular Alaskan politician. As political analysts observed at the time, Peltola beat Palin, not with a polarizing campaign, but by “forging a coalition across class, party and ethnic lines,” and once in Congress, she stressed the importance of bipartisanship. In the most recent November 2024 election, while Peltola was among the many Democratic incumbents that lost, she finished 5 points ahead of Harris, whom Peltola had declined to endorse to further broaden her moderate appeal.

In short, the leading anecdote trotted out to show how RCV enables polarization actually tells the opposite story. It showcases a winner who fully embraced moderation and coalition-building. To his credit, even Condorcet proponent Ned Foley now admits that the 2022 Alaska races show that RCV can “combat polarization and elect candidates who are closer to the center.” With no other recent center-squeeze anecdotes available, he is now leaning heavily on pure hypotheticals, like “what if incumbent Republican Senator Rob Portman had run for reelection?” None of the hundreds of real RCV races over the past several years will do. Certainly the RCV elections to the Alaska state legislature won’t make the point, as a bipartisan compromise coalition has now captured both of its houses.

Furthermore, where is the real-world data that makes the affirmative case for Condorcet? While it is true that practical use of Condorcet methods is limited, it isn’t zero. It was used for city elections in Marquette, Michigan in the 1920s, for example. How did that experiment work out? Was it a force for moderation while it lasted? Why did it end? And how have Condorcet methods fared for private organizations that have tried them? Condorcet proponents have produced virtually no research into these experiences. These are useful, if not necessary, questions to answer before advocating the broad adoption of Condorcet method for high-stakes governmental elections.

Comparing Campaign Incentives

But for the sake of argument, let’s put aside the practical data analysis and look purely at the theoretical case. Conceptually, Condorcet proponents do have a point: in a center squeeze situation, the candidate closest to the median voter is more likely to win under a Condorcet method than RCV. However even in the theoretical plane, that's not an open and shut case. It’s a fundamentally incomplete argument, because neither polarization, nor its inverse, moderation, spring up from single, isolated elections; they evolve over a period of time due to the various political forces in operation. When we extend our gaze beyond single elections to the broader electoral incentives at play, a very different picture emerges, one in which Condorcet isn’t the tool to promote depolarization that it may appear to be at first blush.

To see why, let’s return to that Alaska example and ask an important question. Namely, why did Peltola run such un-polarizing campaigns in the presence of two potential center-squeeze scenarios in 2022? Her campaign logic was obvious: she needed to win a large fraction of Begich’s supporters to rank her second in order to best Palin in the final round and win the election. That was her most likely path to victory.

It was therefore advantageous for her, and for her constellation of supporters and promoters, to appeal to the concerns and issues voiced by the Republican Begich. As Professor Benjamin Reilly and others have repeatedly documented, RCV tends to exert this kind of centripetal political force in divided societies.

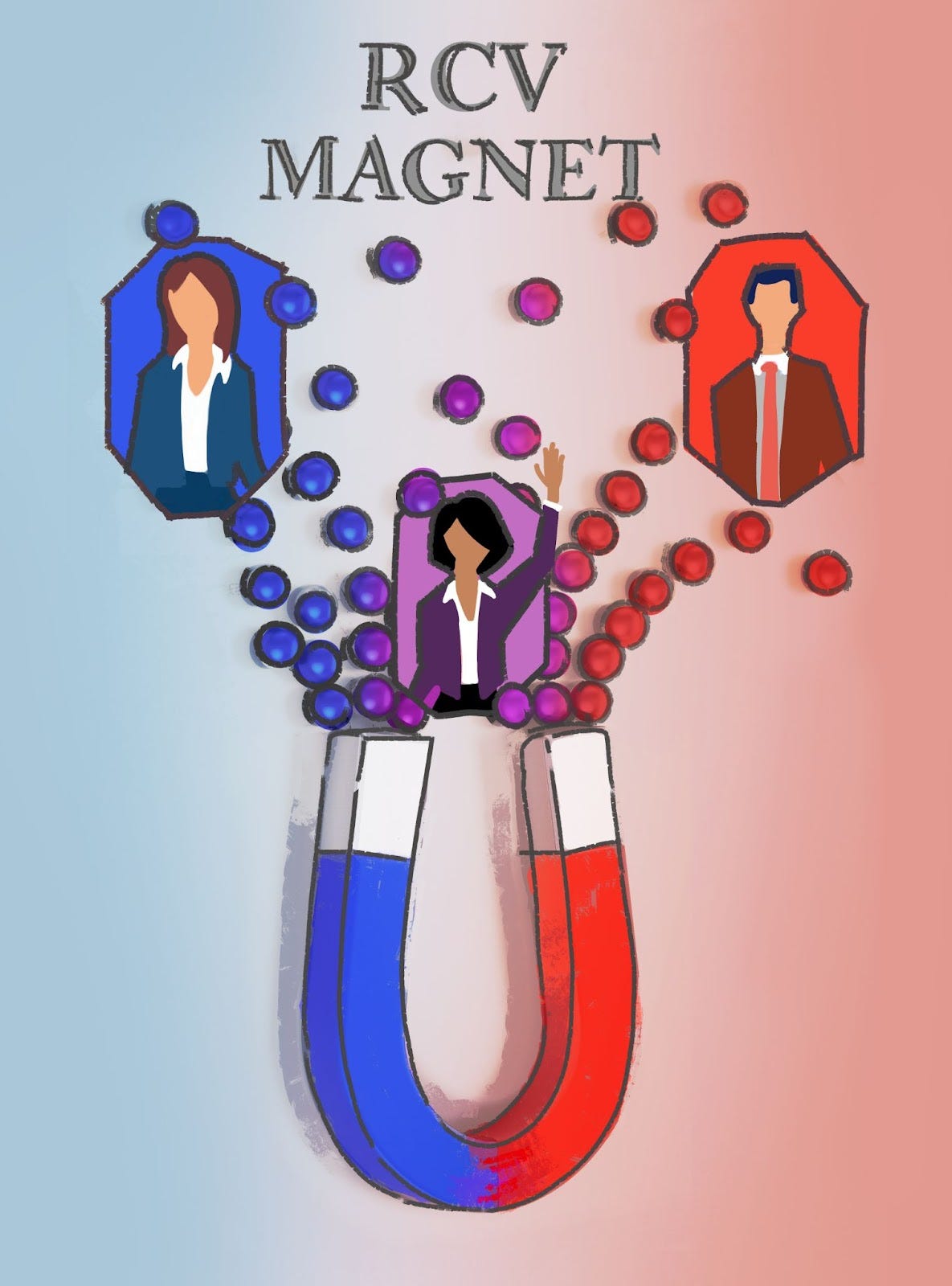

Under RCV, if a potential center-squeeze scenario takes shape, picture that Center candidate as a magnet that attracts the Left and Right poles inward. If candidates Left and Right are smart, they and their respective supporters will appeal to the supporters of candidate Center to earn more 2nd choice rankings. The Left and Right campaigns have an incentive to seek common ground with the Center candidate, offer policy concessions where possible, and generally behave in a more civil and respectful manner towards Center. That’s precisely what Peltola did in 2022, and equally importantly, what Palin did not do.

With the introduction of a Condorcet method, those centripetal forces would disappear from any center-squeeze scenario. If the Alaska race used Condorcet, Peltola and Palin would not improve their odds by earning more second choice rankings of Begich supporters. In a center squeeze, second choice rankings from the Center do not bring the Left and Right candidates any closer to victory, and therefore centrist appeals and moderating rhetoric are of little value.

More problematic incentives would likely emerge in Condorcet elections instead. As Left and Right would soon discover, in a center-squeeze configuration they have an incentive to encourage their respective supporters to “bullet vote,” meaning rank them first and leave the rest of the rankings blank. While bullet-voting offers no advantages to candidates under RCV, under Condorcet it could take the Center candidate out of the running, effectively setting up a plurality-style contest between the Left and Right candidates where they might stand a better shot at winning. To justify the bullet-voting strategy, candidates Left and Right would likely spike their rhetoric with dismissal and demonization of the Center candidate and centrism generally.

Bullet voting wouldn’t be the only problematic incentive. Without any value in persuading the center, the Left and Right candidates would focus on amplifying their base turnout and mobilizing voters further to the extremes. Expect more red meat rhetoric and maximalist positions under Condorcet as a consequence. Worse still, these polarizing effects might be reinforced in election after election, repeatedly cleaving the electorate and pulling the coalitions further apart in both policy and rhetoric. Far from the centripetal effects of RCV, we could see strong centrifugal forces at play, of coalitions and voters moving away from the political center. If RCV turns the Center candidate into a magnet, under Condorcet that candidate becomes the center of a merry-go-round, propelled by every election and flinging its riders to the edges of the platform, if not off it entirely.

A Condorcet proponent may counter that polarization of the coalitions wouldn’t matter, because the Center candidate will ultimately win regardless. But how long can that center hold? It could easily lead to either of two ugly outcomes: first, a candidate from the Left or Right coalitions might succeed in their base turnout strategy and eke out a majority over the Center candidate. A polarized coalition with a mandate would be a scary result, but perhaps not the most likely one. A second and perhaps more probable outcome is that the Left and Right coalitions gang up on the Condorcet system itself and repeal it altogether. After all, in a center-squeeze configuration, neither major coalition gets their way in the outcome, and together they have an absolute majority to undo the reform via a ballot measure.

Conclusions and Predictions

At the end of the day, a conceptual analysis of elections is only as good as its ability to explain real-world outcomes. By this standard, an analysis that warns about an abundance of center-squeeze scenarios and potential polarization under RCV is a dud. An analysis that contradicts the actual results and practical effects of RCV in Alaska, Australia, Northern Ireland, and elsewhere offers little explanatory power. When a theory doesn’t explain reality, it’s time to find a new theory.

Fortunately, we have another theory handy: the one outlined above that focuses on the comparative campaign incentives under RCV and Condorcet. Under this theory, center-squeeze scenarios would be at most transient conditions under RCV, because its incentives would depolarize these conditions out of existence when they crop up. While RCV may permit a non-Center candidate to win on rare occasions, its centripetal effects eventually bring the electorate to rest at a depolarized equilibrium. This theory, in contrast to the one forwarded by Condorcet proponents, aligns quite well with the data from real world elections, stretching back 100 years in the cases of Australia and Ireland.

The theory additionally predicts that when presented with a center-squeeze configuration, a Condorcet method may well amplify polarization and this amplification may result in its own undoing. While RCV enlists the candidate and the candidate’s supporters in appeals to the center, Condorcet enlists them in appeals to the extremes. It’s doubtful that the system itself can withstand the division that will ensue. And the merits of a Condorcet system mean nothing if the system itself cannot be sustained.

The preceding predictions about the behavior of Condorcet are just that—predictions. Claims about the practical effects of a voting system, in the absence of real-world data, should be offered with a healthy dose of humility. Unfortunately, gathering that data on current and past Condorcet use is homework that its advocates have yet to turn in. Then again, perhaps a key reason why there is limited real-world experience to study is that Condorcet can’t reach a stable equilibrium in a competitive, political context. Perhaps the merry-go-round invariably breaks down, and is then replaced with an entirely different ride.

Greg Dennis @VotingNerd

Related: “Alaska election results show why Condorcet is obsolete: Condorcet advocates use the wrong standard for evaluating Ranked Choice Voting elections”

"Even if one believes that center-squeeze scenarios weaken RCV’s propensity for moderating our politics, it’s implausible that they could be consequential at such a low frequency. Those who insist otherwise owe us either a careful argument as to why such rare events could have a substantial impact, or an argument as to why they might be more common in the future."

I agree. Here's my argument for why center squeezes have a substantial impact despite occurring infrequently: https://medium.com/@voting-in-the-abstract/rarely-occurring-pathologies-can-frequently-be-relevant-9b9dc8e9fe22

Moving beyond the frequency of center squeezes, the central argument of this post is poorly reasoned.

"If the Alaska race used Condorcet, Peltola and Palin would not improve their odds by earning more second choice rankings of Begich supporters."

This can only be true if Begich is a strong enough frontrunner that the probability of Palin and Peltola tying for first is negligible. If (say) Palin and Begich are competing for first, then under Condorcet they each have a strong incentive to appeal to to Peltola's supporters - an incentive that does not exist under RCV unless Peltola is liable to be eliminated in the first round. These incentives for Republican candidates to appeal to Democratic voters (and vice versa) are incentives against political extremism.

Alternatively, suppose Begich isn't a frontrunner (maybe he's a lot less popular in general in the alternative reality), and Palin and Peltola are the leading candidates. In that case, Condorcet provides every bit as strong of an incentive for Palin and Peltola to appeal to Begich's voters. In order to be the Condorcet winner, Peltola needs to have more voters rank her ahead of Palin than there are voters ranking Palin ahead of Peltola, and it doesn't matter whether these voter's first choice is Peltola, Begich, or a write-in. The claim the second-choice rankings are valuable under RCV, but not under Condorcet, is completely false.

"As Left and Right would soon discover, in a center-squeeze configuration they have an incentive to encourage their respective supporters to “bullet vote,” meaning rank them first and leave the rest of the rankings blank."

If Palin tells her supporters to bullet vote, that helps Peltola win; it does not help Palin. Palin getting her supporters to bullet does not cause her to be ranked higher than her opponents on any ballots, so it cannot help her become the Condorcet winner. Maybe you're claiming that Palin and Peltola would make a "deal with the devil" to tell each of their supporters to bullet vote, but individual voters are best off not heeding such suggestions.

"While bullet-voting offers no advantages to candidates under RCV, under Condorcet it could take the Center candidate out of the running, effectively setting up a plurality-style contest between the Left and Right candidates where they might stand a better shot at winning."

Even if there is a deal between the more extreme candidates to promote bullet voting and this successfully takes the centrist out of contention, it doesn't mean there would be a Plurality-style contest between Left and Right. Instead, it would be an RCV-style contest, with both the Left and Right candidates competing to be ranked higher than the other by the Center candidate's supporters.

I do agree with you and Ned Foley on one point: RCV provides better incentives to reduce extremism than Plurality. My research that found that Condorcet methods offer much stronger incentives for depolarization than RCV also found that RCV has better incentives than Plurality (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S026137942400057X).

Now, one thing that is disingenuous, is to represent "The Case for Condorcet Voting" with an example that is cherry-picked to make the Condorcet results appear nonsensical. Now I presented the case for Condorcet RCV *solely* as the case for RCV. The very reasons we want Condorcet RCV are the stated reasons that RCV advocates make for RCV, yet those RCV advocates are usually plugging Hare or IRV.

Now the reason to use a Condorcet-consistent method to tally the vote, instead of Hare, is to prevent a failure of IRV to respect majority rule and the equality of our votes. This failure does not happen often, but when it *does* happen, the consequences are *never* good. So I will cherry pick (or make up) another example to show this. But I will not disingenuously call this "The Case for Hare (Instant Runoff) Voting". This is presented to point out the essential flaw of IRV instead. And that case is that of a close 3-way race, so my example is gonna make it *really* close. All three candidates are plausible winners.

99 voters in total

34 Right voters

---30 R>C>L

--- 1 R>L>C

--- 3 R only

32 Center voters

---13 C>L>R

---11 C>R>L

--- 8 C only

33 Left voters

---30 L>C>R

--- 1 L>R>C

--- 2 L only

Now that's a pretty close 3-way race. Who should win? Who truly has the most voter support? Who will Plurality elect? Who will IRV elect?

Now the FPTP people will say that Right should win in this close race because more voters prefer Right as their first choice than any other candidate.

The IRV people will say that Left should win because Left is preferred over Right by 46 to 45 votes (after Center is eliminated). Even though Right gets more first-choice votes (barely), Left is preferred over Right by 1 vote (again, barely).

But Center is widely preferred over either Left (62 to 34) or Right (62 to 35). You can call Center "milquetoast" if you want, but the electorate would *greatly* prefer Center over either Left or Right in this extreme example. Neither FPTP nor IRV will see that.

That is the cherry-picked example that really presents the Case for Condorcet.