TimeMachine: So you think coups and stolen elections are un-American?

Trump before there was Trump

When Donald Trump and his co-conspirators tried to overthrow the presidential election in 2020, many Americans, as well as US admirers around the world, expressed shock and dismay. In a time of advancement of illiberal democracies and authoritarian governments, according to Freedom House, even the world’s “paragon of democracy” had taken a perilous step too close to the cliff. When President Joe Biden hosted his “Summit on Democracy,” along with wayward invitees Philippines, India, Pakistan and Brazil, a whiff of hypocrisy and schadenfreude hung heavy in the air.

Yet a deeper familiarity with US history reveals that America has not been immune to domestic coups and stolen elections. I am reading historian Ron Chernow’s Grant, a biography of the Civil War general and 18th president, Ulysses S Grant. Chernow details how the post-Civil War tensions between the defeated Confederates and northern Union victors resulted in a “reconstruction” constantly wrecked by southern insurrection and ex-Confederate attempts to overthrow racially integrated governments. On numerous occasions, elected officials were dragged from their homes and in some cases murdered in the streets; elections were overturned at the point of a rifle. At that time, Grant’s Republican Party was the liberator of slaves, and Grant boldly deployed the military in the postbellum South to enforce black’s newfound rights. The Democratic Party – today’s party of civil rights -- was the protector of white supremacy and enabler of murderous gangs on horseback of former Confederate soldiers who comprised the core of the newly-formed Ku Klux Klan and White League.

In November 1872, just around the time of President Grant’s reelection, a bitter and divisive race for governor of Louisiana occurred between US Senator William Pitt Kellogg, the Republican candidate backed by Grant, and Democrat John McEnery, an ex-Confederate battalion commander. “Although Kellogg emerged victorious,” writes Chernow, “his foes refused to concede the election.… For months, both Kellogg and McEnery claimed to be governor, holding competing inaugural celebrations. For Grant, the standoff presented a baffling dilemma.”

The election was thrown into the Louisiana courts for adjudication. At this time, the South was an extremely violent place where defeated Civil War veterans had returned home only to enact bloody mayhem against the black population and Republican politicians. For these Confederates, the Civil War had never ended, despite Lincoln and Grant’s compassionate terms of surrender, “with malice towards none, with charity for all.” The fact that some of the Republican officeholders were “carpetbaggers” who had moved to the south from the north, and corrupt besides, added to an already palpable sense of southern victimhood and injury. According to Chernow, even President Grant feared traveling to the south because of concerns over violence against him (the memory of Lincoln’s assassination seven years before no doubt still fresh).

In the aftermath of a disputed gubernatorial election, the Louisiana situation quickly deteriorated due to insurgent Klan activity. A prominent businessman, Joseph Hatch, informed President Grant that one night 20 men in disguise ringed his warehouse, emptied more than 100 shots into it, and threatened that unless his business “was moved, that in a Short time they would apply the Torch.” What was his offense? He was known to have voted for Grant, Kellogg for governor and the Republican ticket.

The Democratic candidate McEnery’s supporters had seized the police station, which along with other acts of violence (such as attacking men physically, and burning their homes to discourage them from voting during the previous election) signaled a wholesale breakdown of law and order. Finally Grant, who had been reluctant to show “any appearance of undue interference in State affairs,” was forced to react: “Instruct Military to prevent any violent interference with the state Government of La.”

With the beefed-up military presence, things calmed down some. But that lasted as long as it took for the insurrectionists to re-arm. After a federal judge ruled in favor of the Kellogg slate, “the powder keg of Louisiana politics exploded in April 1873,” writes Chernow. A pitched battle ensued for control of various parts of the state. One of those places was Grant Parish in the Louisiana heartland. Grant Parish had become a hotbed of former Confederate and Democratic Party insurgents. One plantation owner there threatened to expel blacks from homes they rented on his land if they voted Republican. Ballot box stuffing was common. Following the enfranchisement of former slaves, the total population of Grant Parish had a narrow majority of 2400 freedmen, who mostly voted Republican, and 2200 whites, who voted as Democrats. It was an electoral tinderbox.

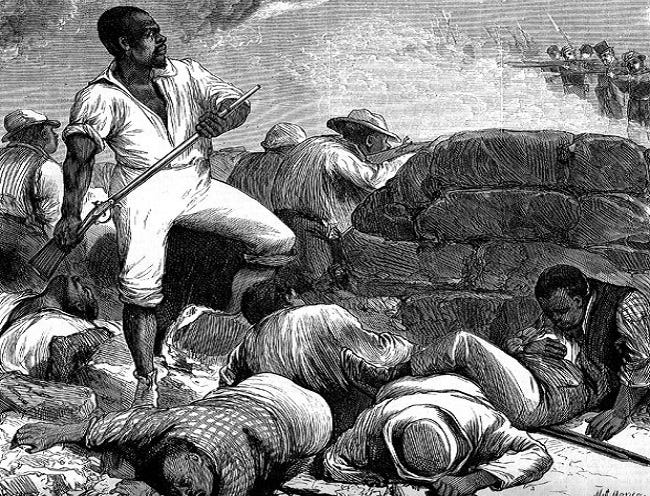

William Ward, a former slave who had fought in the Union Army, was now a black Republican leader in Grant Parish. To prevent an expected takeover of the county seat of Colfax by a private white army led by Christopher Columbus Nash, a formerly imprisoned Confederate officer, Ward summoned his black supporters and they surrounded the Colfax courthouse. They threw up earthworks around the building, dug trenches and drilled their impromptu army to increase their readiness. They held the town for several weeks. Ward wrote to Governor Kellogg, seeking U.S. troops for reinforcement.

But the other side was mobilizing. To recruit men, Nash spread lurid rumors that blacks were preparing to kill all the white men and take the white women as their own. On April 8 the anti-Republican Daily Picayune newspaper of New Orleans inflamed tensions with the following headline:

THE RIOT IN GRANT PARISH. FEARFUL ATROCITIES BY THE NEGROES. NO RESPECT SHOWN TO THE DEAD

Such “fake news” attracted more whites from other parts of Louisiana to join Nash, most of them experienced Confederate veterans. Nash’s growing army also acquired a four-pound cannon that could fire iron slugs. As the Klansman Dave Paul said, "Boys, this is a struggle for white supremacy."

On Easter Sunday, April 13, 1873, Nash led a mob of several hundred whites, armed with rifles and most of them on horseback. They opened fire on Ward and his supporters, blasting away for several hours. With their cannon, they fired on the courthouse, setting it ablaze. Completely outnumbered and outgunned, eventually the black defenders ran up a white flag of surrender. Nash called for those surrendering to throw down their weapons and come outside. Instead of a surrender, what happened next was mass murder.

The white paramilitary group killed every black man they could find, including those hiding in the courthouse. They also chased down and killed those attempting to flee. They dumped some bodies in the nearby Red River. About 50 blacks survived that afternoon and were taken prisoner. Later that night they were executed by their captors. Two state militia colonels sent with warrants to arrest the white leaders found the smoking ruins of the courthouse at Colfax, and many bodies of men who had been shot in the back of the head or the neck from up close, execution-style. One body was charred, another man's head beaten beyond recognition, another had a slashed throat, and almost all had from three to a dozen wounds. Heaps of dead black bodies were scattered everywhere, from the courthouse all the way through town to the river boat landing. Only one black man from the group, Levi Nelson, survived the massacre. He had been shot but managed to crawl away unnoticed. He later served as one of the Federal government's chief witnesses against those who were indicted for the attacks.

No one knows the exact number of murdered, but historians’ guesstimate, from available evidence and testimony, is that 150 Blacks and three whites were killed that Easter Sunday. Historian Eric Foner, a specialist in the Civil War and the Reconstruction era, described the massacre as the worst instance of racial violence during Reconstruction. In Louisiana, it had the most fatalities of any of the numerous violent events following the disputed gubernatorial contest. Foner wrote:

"Every election [in Louisiana] between 1868 and 1876 was marked by rampant violence and pervasive fraud….the Colfax massacre taught many lessons, including the lengths to which some opponents of Reconstruction would go to regain their accustomed authority.”

And then…judicial injustice

But that wasn’t the end of the injustice. Besides being a slaughter ground of white on black racial violence and electoral thuggery, the South during so-called Reconstruction was also a hellhole of rampant judicial prejudice. It was nearly impossible to get a local court to convict white perpetrators for the most heinous acts.

The massacre in Colfax gained headlines in national newspapers from Boston to Chicago. Various government forces spent weeks trying to round up members of the white paramilitaries, and a total of 97 men were indicted. In the end, only nine men were charged and brought to trial for violations of the Enforcement Act of 1870, which had been championed by President Grant to provide federal protection for civil rights of freedmen under the 14th Amendment (the “equality amendment,” passed in1868). The law was supposed to protect Americans against actions by terrorist groups such as the Klan (the Grant administration also passed the Ku Klux Klan Act to combat the Klan and its copycat organizations as domestic terrorists).

The men were charged with only a single murder (plus charges related to a conspiracy against the rights of freedmen). There were two jury trials, both in 1874. In the first, one man was acquitted and a mistrial was declared in the cases of the other eight. In the second trial, a federal jury found three men guilty of sixteen charges; however the presiding judge, Joseph Bradley of the US Supreme Court (who participated in the federal retrial as a second judge while riding circuit, as justices did in those day), dismissed the convictions. He ruled that the federal Enforcement Act they were charged under was unconstitutional (“void for vagueness”) and that the prosecution had failed to prove a “racial rationale” for the massacre. He ordered that the men be released on bail. Once free, those men promptly disappeared, with all involved learning (yet again) about Southern “justice.”

The federal government appealed the case and it was heard by the US Supreme Court as United States v. Cruikshank (1875). The Supreme Court, on which Justice Bradley also sat, adopted his previous rationale and ruled that the Enforcement Act of 1870 (which was based on the still-new 14th Amendment) applied only to actions committed by the state, and was not applicable to actions committed by individuals or private conspiracies. This meant that the Federal government could not prosecute cases such as the Colfax killings, and plaintiffs had to seek protection inside the state’s jurisdiction. Ten years after the Civil War, the supremacy of states’ rights had come roaring back with a vengeance.

This notorious ruling continued the greatest miscarriage of justice, for it not only exonerated massive crimes and cold-blooded murder but established a federal legal precedent that would protect Klan-type activity, and take the first major step toward establishing the brutal Jim Crow apartheid regime that would dominate US politics for the next 85 years.

This was just the beginning of the post-Civil War unraveling of racial justice for black Americans. Predictably, Louisiana did not prosecute any of the perpetrators of the Colfax massacre. President Ulysses Grant was enraged that the southern Democrats, who readily accused him of unwarranted federal intrusion, stood by in the face of such brutality and racism. The president wrote:

“Insuperable obstructions were thrown in the way of punishing these murderers…Every one of the Colfax miscreants goes unwhipped of justice, and no way can be found in his boasted land of civilization and Christianity to punish the perpetrators of this bloody and monstrous crime.”

For Grant, an ex-general who had commanded armies and whose god-like words had meant death for tens of thousands of soldiers, and whose mighty elected office had declared martial law in certain southern states, his inability to protect the black freedmen from the persistence of Southerners’ racist evil haunted him during his presidency and for the rest of his life.

The publicity about the Colfax Massacre and subsequent Supreme Court ruling was like a gunshot heard ‘round the world, launching the proliferation of new white paramilitary organizations. In May 1874, Nash formed the first chapter of the White League, and chapters soon were formed in other areas of Louisiana, as well as in nearby states. Unlike the former KKK whose members wore hoods and operated in secret, the new groups sought publicity and operated openly. One historian described them as "the military arm of the Democratic Party."

This was just the beginning of the terror to come. Domestic terrorist groups used violence, murder and intimidation to win election after election and slowly retake the South. In August 1874, the White League threw out Republican officeholders in Coushatta, Louisiana, assassinating six whites and five to 15 freedmen (the number is disputed) who were witnesses in what has become known as the Coushatta massacre. Although twenty-five men were arrested, none were brought to trial.

Finally, on September 14, 1874, the former Democratic lieutenant governor of Louisiana led a coup attempt when thousands of whites, many of them former Confederate soldiers, barricaded the streets of New Orleans, overpowered a black militia and attacked the racially integrated Metropolitan Police Force which was led by James Longstreet, one of the foremost Confederate generals of the Civil War. They occupied City Hall and the state house, killing more than 20 people. The mutineers announced that Governor Kellogg had been overthrown. Grant dispatched 5000 troops and three gunboats, and only this federal military intervention reinstated Kellogg as the rightful governor.

According to an investigation in 1875 by Gen. Philip Sheridan, “2,141 Negroes had been killed by whites in Louisiana and 2,115 wounded” since the end of the Civil War, yet no one had been punished for those crimes. Such violence, when combined with the failure of the police and the courts to enforce the law, served to intimidate voters and officeholders alike. By terrorizing the freed slaves as well as white Republicans throughout the South, white supremacists repressed voting all during the 1870s and 80s.This became the primary method that white Democrats used to gain control of the Louisiana state legislature in the 1876 elections, and ultimately to dismantle Reconstruction all across the South following the hotly disputed presidential election of 1876, which led to a deal to withdraw all federal troops from the South.

Lessons learned: the South won the Civil War, not the North

What should we learn from this vicious and dehumanizing history? The most important lesson is the most disturbing. We are taught in school, by teachers and in all the history books, that the North won the Civil War. But that is not true, the South did. Because the Civil War did not end in 1865. It continued for the next 10 years in the form of guerrilla warfare, and in the end both President Grant and the war-weary North lost their nerve and willingness to confront Confederate evil.

Black civil rights enjoyed a few brief “golden years,” during which black officeholders, business leaders, farmers, families and schoolchildren made impressive gains toward integration into a new America straining toward a national vision of “charity for all.” And then, under the constant pressure of Southern racism and the failure of the North (which suffered from its own brand of racism) to remain steadfast in its commitment to equality and justice, the election of 1876 snuffed it all out. What came next was the most vicious system of racial apartheid, known as Jim Crow, and it lasted for the next 90 years.

William Briggs, author of “How America Got Its Guns: A History of Gun Violence in America,” and co-author Jon Krakauer have written:

“A straight line can be drawn from Colfax and Cruikshank to the race riots in East St. Louis in 1917 and in Omaha, Chicago and other cities two years later; to the abhorrent crimes committed in the 1921 Tulsa race massacre; to the criminal brutality unleashed on African-Americans in Selma and Birmingham, Ala., in the 1960s; to the present-day instances of police and white nationalist violence in Ferguson, Mo., Charlottesville, Va., and now Kenosha, Wis.; to the shameful, plain-sight attempts to suppress the Black vote in the 2020 elections.”

In Colfax, Louisiana, still to this day, stands a 12 foot obelisk monument in the local cemetery, two blocks off Main Street, honoring the whites who massacred Black Americans 149 years ago. An inscription carved into its base declares it was “erected to the memory of the heroes” who “fell in the Colfax Riot fighting for white supremacy.”

That stings, even today. As Southern novelist William Faulkner once wrote, "The past is never dead. It's not even past.”

Steven Hill @StevenHill1776