To Split or Not to Split: The Negatives of Vote Splitting on Diverse Representation

Ranked Choice Voting can "unify the vote" from traditionally underrepresented communities, even when multiple candidates run

With more women running for office than ever before in our nation’s history, many are confused as to why election outcomes aren’t reflecting this shift by electing more women. The reason is simple: it’s a structural problem of our “winner take all” electoral system.

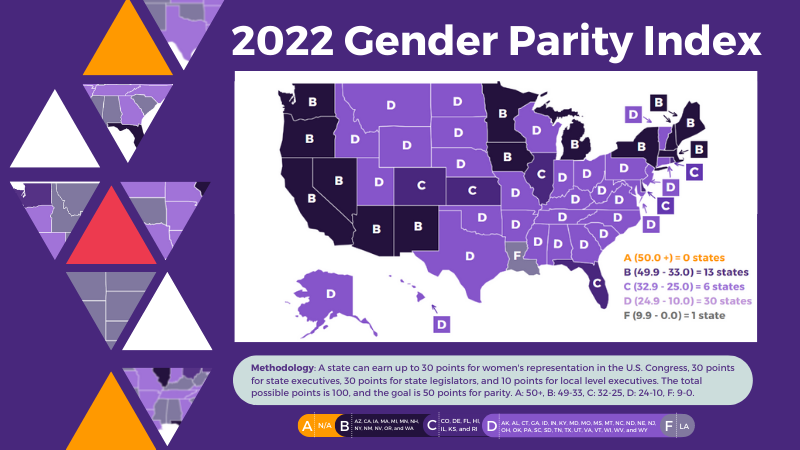

RepresentWomen’s recent release of the Gender Parity Index makes it abundantly clear that, despite more female candidates, we are far from reaching gender balance at all levels of government. It is going to take structural solutions to overcome the insurmountable obstacles that women candidates face in today’s politics.

Vote splitting undermines women’s representation

Did you know that, in our current single- winner plurality voting system, it can be detrimental for parties to have more than one woman run? Simply put, vote splitting is the dilution of power that occurs when several similar candidates run on the same party platforms, and one winner “takes all” of the representation. Vote splitting is a problem for non-status quo candidates in our winner-take-all system, and is a reason why we haven’t yet reached gender balance. In 99.9% of elections in the US, voters are allowed to choose only one candidate, and are prohibited from taking into consideration other second or third choice options.

Think about it: we have an abundance of choice in our grocery stores, with 10 brands of detergent and breakfast cereal, and thousands of choices when shopping online, but when it comes to our politics there is practically no choice at all.

The anatomy of split votes

Take a look at the hypothetical election in this diagram:

Even though Party A has 60 percent of overall voter support, with two of its candidates each having 30% of the vote, Party B ends up winning the election with only 40 percent. This is because the supporters of Party A divided their votes among two candidates, splitting that party’s overall majority support. Vote splitting is present in general elections and primaries, especially when there are more candidates that are running on similar values or representing similar interest groups.

This negative effect is most felt by candidates and party leaders, but voters can also feel it in the struggle to choose just one candidate. This phenomenon disproportionately impacts women candidates and candidates of color who are more often asked to stand down and “wait their turn” rather than run against a preferred candidate and split the vote. Party leaders often will pressure the candidate from their party seen as least likely to win into bowing out. Political parties are unfortunately less likely to support a woman running over a male candidate. This pressure often includes pulling their PAC and financial support. So even while more women are running for office, women and people of color are the first to be pushed out of many races.

The rise of extreme candidates, courtesy of vote-splitting

Now, you may be thinking your alternate candidate choices are irrelevant, seeing as only one candidate can win an election. Doesn’t the current system of single-winner plurality voting incentivize voters to simply choose the most qualified candidate? Unfortunately, it’s not that simple.

Under our current system, the more some candidates take similar positions on the issues, the more prone they are to vote splitting. This in turn allows extremist candidates to have higher chances of being elected. Since they have a strong core of diehard supporters who will vote only for them, once the majority constituency splits its vote among too many candidates that allows extremists to win with minority support. This is especially true in primary elections, which often have extremely low voter turnout of around 20-30%, with the most motivated and hyper-partisan voters showing up. That allows a strong motivated core of extreme voters to maximize their impact.

In Nevada, Sheriff Joe Lombardo won the Republican primary for governor with 38% of the vote. In Ohio, celebrity author J.D. Vance won his Senate primary with 32%, and in Arizona Blake Masters won the GOP primary with 40%. All deny that Donald Trump lost the 2020 presidential race to Joe Biden, and these candidates rallied the pro-Trump minority to win their race over more moderate GOP candidates.

Since most legislative districts are so lopsided for either Democrats or Republicans, once a candidate wins a low turnout primary, that candidate is virtually guaranteed to win the lopsided district in the November election. Consequently, as found in a report from Unite America, just 10% of eligible voters nationwide cast ballots in primaries in 2020 that effectively decided 83% of U.S. House races. Our primary system of nominating party candidates not only is contributing to minority rule in the US, it is also a breeding ground for extremists.

An increase in extreme candidates also can contribute to a rise in negative campaigning, which tends to drive up costs of campaigns. Both of those factors contribute to inhospitable conditions for women who are considering a run for office. In fact, recent research suggests that negative campaigning can deter women from running all together. This is a huge step back for gender balance in elected offices. As might be expected, with more radicalized candidates utilizing negative campaigning strategies, the hostility in politics is magnified and polarization continues to escalate.

With all of these barriers perpetuated by vote splitting and the current single-winner plurality system, it’s no wonder more women aren’t being elected. If women are continuously discouraged from running, or remain unsupported by their party due to the fear of their losing an election, how will women ever reach gender balance and ensure that the best and the brightest are leading our democracy?

The way forward

Moving forward, it’s time to try something new. All of these issues stem from the structure of our single-winner plurality voting system. We need an improved voting structure based on two changes: first, use ranked choice voting instead of plurality voting. When New York City used RCV for the first time in 2021, a political earthquake occurred. Women had never held more than 18 seats on the 51-seat city council, and women of color never won more than a handful. Now women hold 31 seats, filling 61% of the council seats, and 25 five of them are women of color.

Under ranked choice voting, voters rank candidates in order of preference, marking their favorite candidate as their first choice and then indicating their second and additional back-up choices in order of preference. Voters may rank as many candidates as they want, with the knowledge that indicating a lower ranked candidate will never hurt a more preferred candidate, and that you are not wasting your vote on a candidate without a lot of support. In many NY City races, multiple women candidates were able to run without being plagued by vote-splitting or charges that they were spoiler candidates. So now New York's city government has a female – and nearly a woman of color – majority, making history in the nation's largest, most diverse and most influential city.

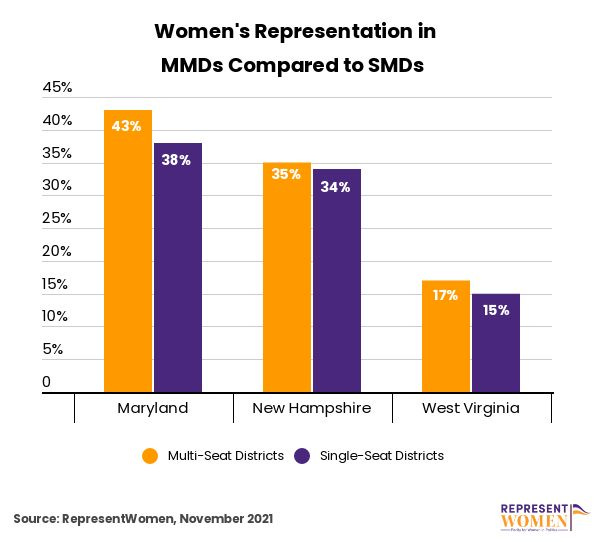

Second, use multi-winner districts instead of single-winner districts. Research from RepresentWomen shows that female candidates tend to do better when running in multi-seat districts than single-seat. Multi-winner districts eliminate having a single winner for each district, instead allowing multiple people to represent the same district. That frees up more voters to feel like they can cast a vote for a female candidate. As the chart below shows, in states that use both multi-seat districts and single-seat, women do better in the multi-seat districts.

Going a step further, by combining multi-seat districts with ranked choice voting, candidates can be elected by a system of proportional representation. This PR system lowers the “victory threshold,” which is the percentage of votes it takes to get elected. Instead of needing a majority of the vote to win one seat, a candidate would need 20 percent of the vote in a four-seat district or 25 percent of the vote in a three-seat district. That would really open up the elections to allow a more diverse gallery of candidates to get elected.

When you combine multi-seat districts and ranked choice voting into a system of proportional representation, then more varied candidates have the opportunity to run and win and voters have the opportunity to express their preferences for multiple candidates. This in turn allows elected officials to better represent the diversity of opinions and values of their constituents, and allows for a wider variety of voices to be heard.

A legislative path forward

The Fair Representation Act incorporates both multi-seat districts and ranked choice voting. When it becomes the law, women will more than likely win better representation, as will people of color, especially women of color. RepresentWomen’s research found that the Fair Representation Act has the ability to increase the projected power to elect for Latinx people in the US House of Representatives by 41 percent; it could increase the projected power to elect for African Americans by 26 percent and Asians by 200 percent (see the chart below). Ultimately, the passage of the FRA and the incorporation of new systems strategies will lead to elected House members that more accurately represent the majority opinion and will foster a healthier, more gender-balanced democracy.

Haley Silva